By Michael Eric Dyson

1996

Conversations with smart people about stuff that affects our world, and how we affect it

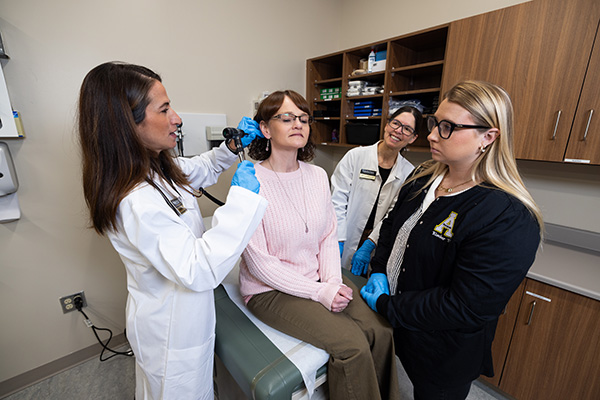

In a recent visit to Appalachian State University’s podcast studio, one of America’s foremost African American voices, Dr. Michael Eric Dyson, shares his thoughts on 21st-century activism, and the value of empathy.

In a recent visit to Appalachian State University’s podcast studio, one of America’s foremost African American voices and renowned public intellectuals, Dr. Michael Eric Dyson, shares advice on how to affect change, government and academic leadership, activism and speaking up.

Transcript

Megan Hayes: One of the nation’s most renowned public intellectuals, Dr. Michael Eric Dyson has been named one of the most inspiring African Americans in the United States by Essence magazine and one of the most influential Black Americans by Ebony magazine. Called a “street fighter in a suit and tie,” he takes on the toughest and most controversial issues of the day including race politics and pop culture with his fearless and fiery rhetoric. An MSNBC former political analyst and former host of NPR’s “The Michael Eric Dyson Show,” Dr. Dyson is also an award-winning author; his speeches and books provide some of the most significant commentary on modern social and intellectual thought today, interwoven with a combination of culture criticism, race theory, religion, philosophical reflection and gender studies. Dr. Dyson has authored or edited 18 books, which explore the deep complexities of race, class, and gender dynamics as they manifest in American culture. His first book “Reflecting Black: African American Cultural Criticism” published in 1993, helped establish the field of Black American Cultural Studies. Two years later his book, “Making Malcolm: The Myth and Meaning of Malcolm X” was named one of the most important African American books of the 20th century. His latest book is “The Black Presidency: Barack Obama and The Politics of Race in America.” An ordained baptist minister since the age of 19, Dr. Dyson holds a PhD in Religion from Princeton University and has taught at Chicago Theological Seminary, Brown University, Columbia University, and the University of Chapel Hill, among others. Since 2007, he has been a professor of sociology at Georgetown University, and, as I understand, a very popular one. I think we are about to see why. Dr. Michael Eric Dyson, welcome back to Appalachian. I think you were last here in 1997.

Dr. Michael Eric Dyson: Yes, I know it’s been almost 20 years. It’s great to be back.

MH: Well, welcome back to campus and welcome to SoundAffect.

DMD: Thank you.

MH: I’d like to begin by talking about something that is taking place on our campus right now. Over the past year and a half members of our campus community have, like many other universities, held demonstrations and public discourse focused on race, privilege and marginalization. Just in the past week students here have voiced their opposition to the recently passed public facilities, privacy and security act or HB2 with public demonstrations on our campus and in the community. But while HB2 is bringing new fears to the forefront but, the issues our students are bringing forward are not really new, they are issues of marginalization, discrimination, tokenism that our predominately white campus is working through as we actively face the challenges of diversifying our community. Our students are looking for a next step, and they are asking what can they do and how can they affect change. While I realize you are not privy to the specifics of our challenges, these are somewhat universal. I was wondering if you had some advice for our students and our administration about taking the next step from demonstrating to action.

DMD: I think it is extremely important issue to be addressed. And I think first of all drawing the parallels between struggles against injustice in other arenas and spheres and making those connections here. Martin Luther King Jr. said, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” Racial injustice is intolerable, but so is the injustice directed toward gay, lesbian, transgendered, bisexual, queer people, those who are women as minorities in predominantly male environments, and those who are other-abled and the like. We have to pay attention specifically to the interest of those people and to see that their democratic rights are protected, small ‘d’. I think the place we go from here is, not only conceiving of an invigorating response against the injustice, which is important — a publicly powerful, symbolic fashion of expressing outrage against what has occurred — but on the other hand, I think it has to move into a different sphere and that is the electoral one. How do we hold politicians accountable who have passed these laws and who have put this legislation forward? A governor who has signed it or the legislators that articulate it? I think similar to what we saw in what I believe was Cleveland, Ohio and Chicago, Illinois, where local prosecutors made decisions that were counterproductive to racial harmony and racial justice by not calling to account in Cleveland the cops who killed Tamir Rice and in Chicago, a long delay in the case of Laquan McDonald who was killed by a policeman there. They took to the polls and they put those people out, so I think the next logical step is to leverage the authority of one's own civic and civil participation and make certain those people who make those decisions are held to account. Secondly, to flood them with calls, emails, tweets, letters and the like to express the profound displeasure with what they see occurring here. You can be certain that those who support that law have expressed it, and voluminously. So what they have to do, that is those who protest against HB2, is to figure out a way to express themselves by flooding the channels of democracy with their presence. Thirdly, I think what has to happen is people have to vote even more broadly, not simply for a president and not simply for prosecutors, but at every level, for all of the legislators that are put into office. How can we hold them accountable and have local meetings beyond the protest, where citizens either go to the city council or the local state senator and flood those with bodies of protest and, then beyond that, call out community organizations — the NAACP, the Human Rights Watch and the like who together can leverage their collective presence as watch groups, watchdogs of local rights and national ones as well — and push those forward in public meetings where citizens are able to express what they believe. I think those are some of the ways people can take action beyond the protest.

MH: Our students are connecting Black Lives Matter to this movement, broadening it beyond a LGBTQ+ discussion because it is a symptom of larger oppression. Do you think this inclusion is emblematic of a new millennials form of activism or maybe the next step put in place by Dr. King connecting the Civil Rights movement to poverty.

DMD: I think that’s great and I think both are true. This is a logical extension of what Dr. King talked about in terms of fighting militarism, of fighting poverty and of fighting racism. At the end of his life he was preoccupied with this very aggressive/progressive agenda and he was not very popular as a result of that, but he continued to forge ahead. I think that the millennials are certainly on cue when they are taking their marching orders from both the history that they have studied, but also the contemporary moment that calls out its own unique action. Their emphasis on intersectionality, the ways in which race, class, gender and sexuality and the like come together and must be dealt with simultaneously, not as individual groups who are segregated or parceled out, but to understand how all of those issues come together simultaneously and therefore must be addressed simultaneously. I think millennials are on top of that and on cue by responding in a very powerful way. It brings together a greater base of allies. The broader that you extend the tent of justice for issues that are impacting human beings and citizens, the broader sway you have, because you have more numbers of people who feel implicated in particular actions and who feel called to respond in a very decisive and political fashion.

MH: One of the things I admire about your oratory style is your combination of part inspiration and part take-no-prisoners. You hold people accountable for their actions and yet you also give them credit where credit is due. I think this is an amazing gift that you possess, but I also have a feeling that it is a deliberately crafted skill as well. Can you take about how you foster this skill and also why it's so important to do that.

DMD: Yeah, well thank you very kindly for your wonderful and generous words. Look, I’ve been part and parcel of the Black church since I’ve been knee-high to a tad-pole. I remember as a young child —3, 4, or 5 years old — participating in the Sunday School recitations during Easter or Christmas and having speaking parts. From there I remember getting involved in spelling bees at school and oratorical contest. Before that, even in the fifth grade with my teacher, Ms. James at Winkler Elementary School in Detroit, she gave us a sense of black history and we studied it and we studied it well. We delved deeply into the recesses and the wells of black history, black thought, black progressive identities that were being put forth by people from Mary McLeod Bethune to Nannie Helen Burroughs to Jackie Robinson and Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcom X. We studied. But I was also able to win my first blue ribbon for the recitation of poetry, “Little Brown Baby,” by Paul Laurence Dunbar, one of his vernacular poems. That public recitation of poetry, public spelling bees and then, in the seventh grade, getting involved in oratorical contests where I went on to win several awards for crafting speeches that we had to memorize and then present after writing them. That then lead me into oratorical engagements across the city of Detroit and then eventually as a preacher across this nation. I’ve been a student of oratory, a student of the best thought that was articulated in a public space by people who were extemporaneously speaking or those who had a prepared document from which they delivered their public remarks. I’ve been a fan and a student of that and have tried to bring together some of the best traditions of black preaching, public oratory, the classroom, the intellectual’s workshop and the intellectual's vocation to unite them to use words as wisely and as provocatively as possible to bring about change.

MH: When you talk about public figures like Martin Luther King and Barack Obama and many others you have this way of providing them with both compliments for what they do well, but you give them a hard time, too.

DMD: I think we have to be balanced. I think Barack Obama is an extraordinary figure, one of the greatest Americans we’ve ever produced. I think he will go down as one of the greatest presidents in our history now that the full arc of his presidency is becoming clear and the accomplishments are pretty noteworthy. But what he is done on race will not win him those plaudits. He is like Shaquille O’Neal. As a basketball player Shaquille O’Neal was a dominant figure. He just got elected into the Hall of Fame after four championships, but he was a horrible free throw shooter. When we tell his story we cannot lie and pretend that he also did well with free throws because he didn’t. He made his team vulnerable and because of his own deficiency in that arena he was a liability to his team at the end of the game. So they did what was called a hack-a-shaq. A hack-a-shaq was to deliberately foul him because they knew he was a poor free throw shooter so he’d be put on the line and therefore he may lose the game. Barack Obama does many things well one of them is not leading with purposcacity, with intelligence or insight on the issues of race. He has those things, but just hasn’t shared them as generously with us as I think might be warranted by the situation, the crises that we see in America right now. What is interesting, is I happen to believe that given what is going in this 2016 race between the democrats and the republicans, we see on the republican side a man who is leading the nomination for the republican side and has in many ways been the leading figure from the very beginning. This same man is the very man who said Obama was not a legitimate American and who lead the birther movement against the president. We see the degree in which we have descended, plummeted even, in our own American democratic experiment with a man now who fancys himself a true leader, but for whom demagoguery or a certain level of xenophobia and racism seem to attach to his rhetoric, whether that is his intention or not. When we think about that, we think about the fact that race will be spoken of, so if you hesitate to speak of it, as the president has, someone will fill that gulf and gap. Unfortunately the people who have filled that gap have not been as insightful, wise, compassionate or as historically knowledgeable as the president. His failure to speak up left a gulf where others stepped in and I think Donald Trump is one of them. That’s one of the poor consequences of his politics of racial procrastination and his deadly hesitation to articulate viewpoints and understandings that might have helped the nation move forward. I think his own racial hesitancy and procrastination have been deleterious, have had negative consequence. I appreciate his genius and his incredible ability to bring people together, but he also has some flaws and, as with Dr. King, we have to be honest about them.

MH: I like, too, how you are honest about people that you don’t agree with in terms of… you’ll give somebody a hard time, but then turn around and say I do like this aspect about what they have to say or who they are. That is something that is so important right now for where we are as a nation.

DMD: Look, if you are going to demonize your opponent then you’ve lost already. The argument has been lost; not necessarily the ones on partisan argument, but the argument that is based upon one's humanity. We don’t have to premise our opposition to our opponents by the denial of their humanity or on the inability to acknowledge them as worthy human beings who happen to disagree, and even vehemently so. I don’t think it does any good to deny our opponents are human beings: “They are not American.They are not really democratic or invested in the same kind of process we are.” Stop. All of us are trying to work our way toward a better America and a better nation. I vehemently and vigorously disagree with many of my opponents who happen to be on the far right, and certainly those who are republican, but it doesn’t mean I deny their humanity and don’t understant that they can say some things. Donald Trump has said some things that I think are interesting when it comes to challenging the status quo when it comes to politics as usual, and how on both sides of the aisle, democrats and republicans, big money has been a wash in there and he is funding his own campaign. What everyone says about that… there's something resonate about that challenge. So many people are picking up not simply on his racism, his xenophobia, and his gender resistance to women and his misogyny. There are also other elements there that are quite powerful and quite resonate that there are judgement of those of us who claim to be on the right side, but haven't necessarily all the way, all the time done the right thing. I think it’s important to see the legitimacy and humanity of one's opponent.

MH: Can you talk about the role of a leader. Whether that be a company, a university, a university system, we just had ours visit today, or a country to will facilitate a culture that will marginalize those who are marginalized.

DMD: That’s beautifully put. Look, leaders lead. That means they take the guff from other people, they take what sticks in somebody else's craw and they have to hear it, they take the finger pointing, the take the denunciation and absorb all of that into their collective body so to speak. What they do is put forth ideas. Imagination is important to foster a climate of openness, the ideas that must be expressed must come from a place of genuine knowledge and insight of about a particular arena but especially if we are talking about higher education, what the nation needs, how it should be driven forward, or if you’re a political figure how we best call upon as Abraham Lincoln said, “the better angels of our nature.” For me leaders are people who are willing to be open minded, they take the best knowledge available and apply it, they are able to listen to others who don’t agree with them and consider their viewpoints as they make decisions. Ultimately then those who are able to take the heat and to stand up and be recountable and responsible for the decisions they make, for the choices they embrace and for the rhetoric they use to express those choices. When we have a self-conscious in that sense leadership that is willing to be self-critical as well as moving the nation, the community, the college forward, then we have the best of what we have done as a people, collectively speaking as Americans, and we are able to move the needle in a more progressive, helpful direction in this nation.

MH: Everyday I ask myself as a parent, a staff member, and someone who teaches college students, what can I do to make my community more inclusive? I think a lot of us ask that question at Appalachian and we are working really hard on that as a university. What advice do you have for those of us who are trying to work through this?

DMD: I think being reflective, meditate a little bit everyday, just think about where we are and what crisis we confront. What problem or obstacle or impediment we need to overcome. When we do that and then from there ask ourselves “Are we doing everything we can to make this nation, this school and this community better? Can we empathize with people with whom we disagree? Furthemore, those people who are vulnerable, are we doing everything we can to relieve the hurt, harm and danger to which they are subject? Do we as oppressed people introduce other forms of oppression?” For instance if you are an African American, Latino or a woman, do you engage in homophobic behavior, because you’re a member of a church? Even though you were a woman who wasn't allowed to speak or a black person who wasn’t allowed to participate or a Latino who had been marginal, when you get the power, do you exercise it in a just fashion or do you reintroduce elements of injustice in the name of your particular group, tribe or organization and end up reproducing the very pathology that we seek to avoid when we speak about justice? I think when we are open, honest and self critical, and imagining the other person whose back is against the wall and is being mistreated, if we can imagine ourselves as them and not get defensive so that when white brothers and sisters are asked to think about white privilege... now, there is a way to ask that question… I don’t think you should beat people down so they are so defensive that no good can come of the conversation. If you ask people to think about what it might mean? “Oh I don’t have any white privilege. I’m poor like everybody else. I came from the holler, the backwoods, out yonder...” Then you say, “Well if you’re a white person though, when the police happen to stop you and you reach for your wallet, they don’t assume it's a gun, that's a form of white privilege that has nothing to do with class.” That extends to people, the presumption that they will not be dangerous or somehow destructive or threatening to a particular police person and that has to do with collective unconscious, that has to do with bias, has to do with who you think is more likely to commit a crime. There are many ways and layers we have to think through. If we are willing to, as I challenged earlier, African American people or Latino people who may be homophobic and challenge their own views. If we are willing to open ourselves to criticism, helpful, principled criticism, not nastiness, not viciousness, not what Taylor Swift calls “haters gonna hate,” as she borrows that from others. The point is, are we willing to be open and honest and exchange ideas and say we disagree and why we disagree and at least to move ourselves to a more enlightened direction? I think at that level, we will represent the best of the traditions that have produced us in this nation.

MH: Dr. Michael Eric Dyson thank you so much for your time. It’s truly been my privelage to speak with you today.

DMD: Ms. Hayes it’s so so wonderful to be here with you. Invite me back anytime I’d love to come back.

MH: Thank you. In a way it was fortuitous that you weren’t here in January and that you came here today. Our campus needed you today and we are so glad that you are here with us.

DMD: I’m honored to be here and privileged to sit here with you. Thank you.

In a recent visit to Appalachian State University’s podcast studio, one of America’s foremost African American voices and renowned public intellectuals, Dr. Michael Eric Dyson, shares advice on how to affect change, government and academic leadership, activism and speaking up.

What do you think?

Share your feedback on this story.

By Michael Eric Dyson

1996

Conversations with smart people about stuff that affects our world, and how we affect it

About Appalachian State University

As a premier public institution, Appalachian State University prepares students to lead purposeful lives. App State is one of 17 campuses in the University of North Carolina System, with a national reputation for innovative teaching and opening access to a high-quality, cost-effective education. The university enrolls more than 21,000 students, has a low student-to-faculty ratio and offers more than 150 undergraduate and 80 graduate majors at its Boone and Hickory campuses and through App State Online. Learn more at https://www.appstate.edu.

![How NCInnovation Is Rethinking Economic Development in North Carolina [faculty featured]](/_images/_posts/2026/02/rethinking-economic-development-600x400.jpg)