BOONE, N.C. — In the current digital age — a time when computer technology quickly and widely disseminates information — when, according to Google, its search engine can comb hundreds of billions of websites in a fraction of a second and return page upon virtual page of results in response to “What is fake news?” — the question arises: Why are physical libraries still needed?

The answers are many, according to Dr. Dane Ward, dean of University Libraries at Appalachian State University, Dr. Ericka Patillo, associate dean of libraries, and Information Literacy and Instruction Coordinator Kelly McBride. The trio pinpoint relationship building, sustainable library spaces and materials, and ingraining of information literacy into the curriculum as the keys for academic libraries to continue successfully serving their communities in a digital age.

Patillo noted that, while Belk Library has transitioned to having a higher percentage and circulation of materials in electronic format than its physical collections, she said the gate count — the number of people coming into the library — has remained consistent. In the 2016–17 academic year, 1.3 million patrons passed through Belk Library’s doors.

She said one way to interpret such data is that “our students, especially, still need the physical space in which to study, and we have a number of ways in which we’ve received this information from students, telling us that they want the physical space to be in.”

McBride said she finds it interesting that faculty, students, staff — even librarians — have what she called a “touchstone” for how they think about the university’s libraries.

“Even though we’re in 2018, we still have people whose experience with libraries predates that by quite a bit, but they’re still coming in,” she said. “There’s something about the community of the library where people feel, perhaps, unlike an academic department, that they own it in some way, in a good way.

“There’s a sense of welcomeness here that may be different from other places, and I think that our campus community still expects that — ‘Oh, I can go to the library’ — whether it’s physically coming into the building or whether it’s virtually experiencing the resources that we have.”

Historically, Ward said, libraries have been the heart of campus, and this positioning is continually being reinvented.

“Libraries have existed at least since 2600 B.C. and have been vital institutions that have adapted to a number of technological shifts and changes,” Patillo said.

“Moving from the clay tablets, to the catalog cards, to our electronic environment — to the digital age — we adapt. We adapt based upon the needs of our users, and also, we employ our expertise to each one of these challenges and opportunities,” she explained. “As long as we keep our finger on the pulse of our users, we’ll continue to be needed to help people interpret all of the information that’s out there.”

Assessing patrons’ needs — new liaison program to be launched

In order to gain further insight into the needs of the Appalachian Community, Ward shared University Libraries will launch a liaison program in fall 2018 to become “more deeply integrated into the curriculum and into the academic and nonacademic departments.”

Ward said a library staff member will be assigned as a liaison to each of the university’s departments, aiding the department’s faculty and staff with locating and obtaining information and materials needed for their courses. These liaisons will also address the information needs of faculty and staff members performing their own research.

He said, in looking toward the future, it’s important for academic libraries to discover “what, exactly, is it that our faculty, our curriculum, our students need to support learning and research. We’re moving away from passive learning to active learning, and this requires a different kind of support from the library.”

Ward said building strong relationships is paramount in learning a community’s needs and making both individual-oriented and collaborative learning happen.

“It’s all about relationships — life’s about relationships, work’s about relationships,” he said, “and this liaison program is going to succeed because of the relationships we have with the departments and the kinds of conversations we have: ‘What do you need for this class? That research assignment you’re giving your students — what do you really expect them to come away with and can we provide that information?’”

Patillo offered an example of a library–community partnership, stating that many public libraries include among their borrowable materials a resource that is particularly difficult to bookmark — seeds.

The Ashe and Watauga County Seed libraries offer free seed packets from which patrons may plant and grow vegetables — including heirloom varieties. Patrons are encouraged to save seeds from their plant yield and return these seeds to the library to promote food sustainability.

“That’s kind of an odd thing for a library to maybe have, right?” Patillo said of seed libraries, “But it’s responding to the needs of their users.”

She said academic libraries must follow suit and consider, “What do our users actually need and how are they actually using, or needing information in new ways? … our 18-year-old undergraduate might have a different way of seeking information than a tenured faculty member, and we have to look and hear from all of them about what their needs are.”

Patillo said she has become a library expert for friends who are also teaching faculty colleagues. “They will contact me when they have a question about a resource or a service.”

University Libraries also fosters broader relationships outside the campus community.

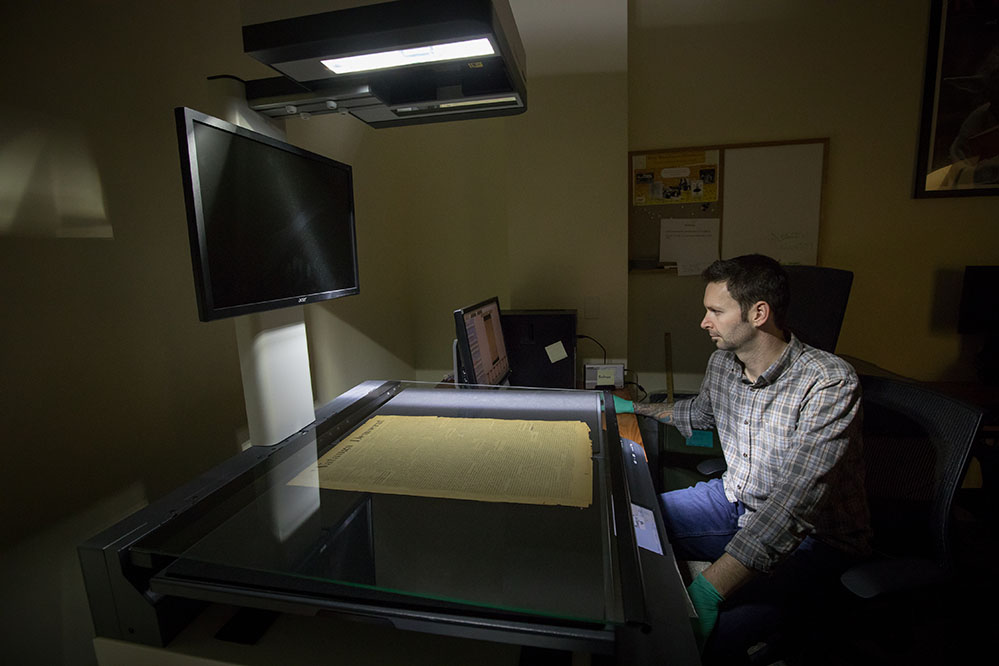

“Public libraries often have access to people who have these incredible collections of images, photos, documents of the history, of the local history,” Ward said, “but they don’t necessarily have the ability to preserve, digitize and make them widely available.”

Academic libraries, he said, do have that possibility with expertise in digitization.

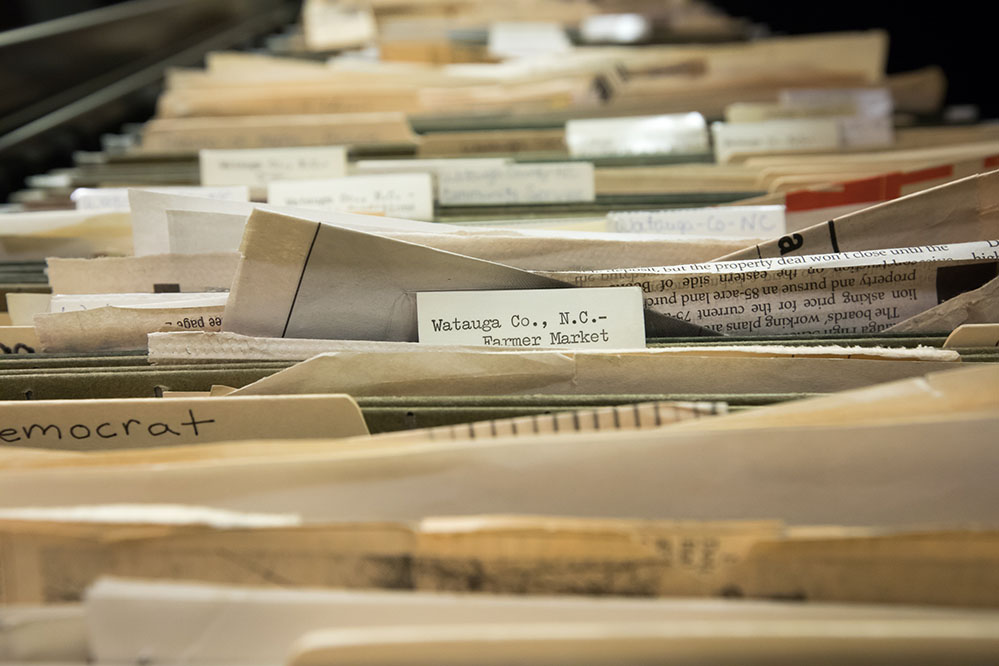

Through the Digital Watauga Project, Belk Library’s Digital Scholarship and Initiatives (DSI) team is helping to digitize every issue of the Watauga Democrat — from the first issue published in July 1888 to the most current issue.

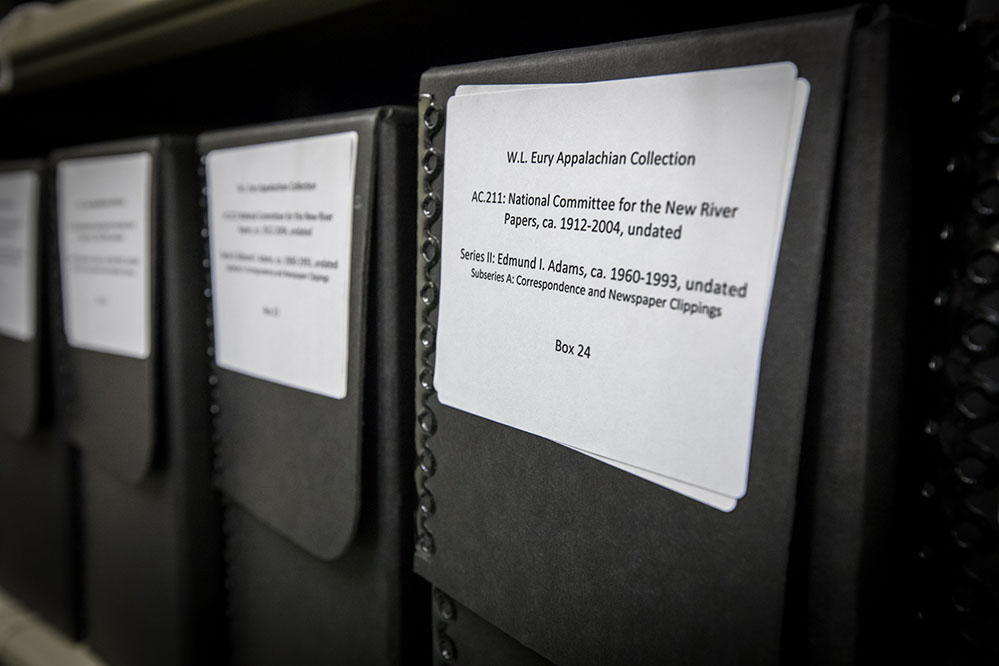

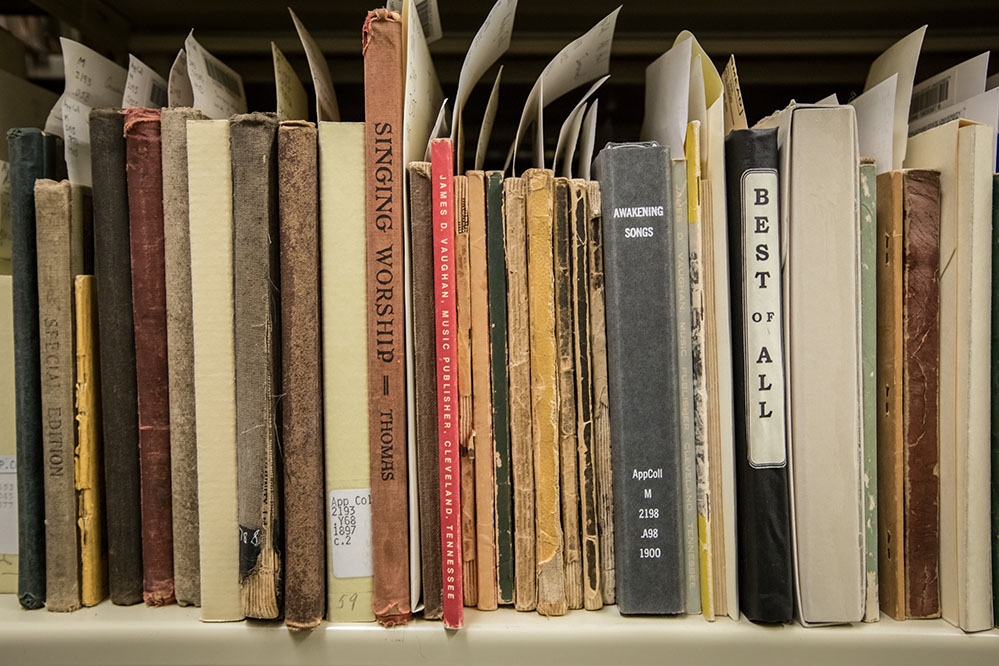

Additionally, the DSI team oversees the long-term preservation of digital materials for University Libraries’ Special Collections, which include the Bill and Maureen Rhinehart Rare Books and Special Collection, the W.L. Eury Appalachian Collection and the Stock Car Racing Collection, along with the University Archives and Records.

The team also assists with project-specific data preservation needs of the Appalachian campus community and for regional, collaborative digital projects. Community partners the DSI team has worked with include the Blowing Rock Historical Society, the Bienenstock Furniture Library and the Lincoln Heights Recreation Corporation.

Shaping sustainable spaces for collaboration

“I think libraries are ideally the place where learning communities happen,” Ward said. “We should focus on creating spaces where students, faculty, staff and librarians can learn, grow and create knowledge together. The question we should ask is not, ‘What are the space needs?’ but, ‘What are the information/space needs for specific groups of people?’

“And if there’s a word that defines libraries in the emerging era, it’s sustainability,” he said.

Twenty years ago, Ward explained, libraries were the only place one could go to discover information because it wasn’t available on the internet. Now, libraries not only serve as storehouses for information, he said, but as collaborative learning environments where campus community members come together to create knowledge.

Ward said the competing demands for space mean that the unending growth of the printed books collection is no longer viable. “We have to hone our collections to the needs of the users by paying attention,” he said.

“The challenge for libraries all across the county is figuring out how to learn what our community, our university community, needs,” Ward emphasized. “It’s pushing us to connect with departments, both academic and nonacademic departments, in ways we haven’t done before.”

Information literacy and library instruction at Appalachian

When considering the roles of librarians in the digital age, Patillo said a quote by English author Neil Gaiman came to mind: “Google can bring you back 100,000 answers. A librarian can bring you back the right one.”

“There’s a deluge of information,” Patillo said, “but it’s meaningless unless you interpret it.”

Belk Library faculty members work with other faculty across all university departments through the Library Instruction program to offer course-integrated instruction that develops students’ competencies in the core areas of information literacy and critical thinking.

“I think information literacy is a developing skill,” said McBride, information literacy and instruction coordinator for University Libraries. “In terms of what is it you’re looking for — is it high stakes, low stakes? — sometimes a particular search might completely meet your needs, but we also know that sometimes, within an academic environment, there are certain expectations about the quality of information. That is a learning process.”

In addition to information literacy instruction, Appalachian students, faculty and staff have access to one-on-one, in-depth research assistance — at any point in the research process — through Belk Library’s Research Advisory Program (RAP).

RAP sessions, which may last up to one hour, can be conducted in person, by phone, or online via web conferencing. According to McBride, in the 2016–17 academic year, 235 individual RAP appointments were made.

The library also offers 17 different online guides that provide help during the research process, as well as overviews of guidelines for various writing styles, grants and funding, defining and avoiding plagiarism, and a guide to Appalachian’s e-book collection.

“I see librarians working with students all the time,” Ward said of the RAP, “and I think there’s a lot of real, powerful learning going on there.”

To learn more about Appalachian’s University Libraries, visit https://library.appstate.edu and https://music.library.appstate.edu.

About University Libraries

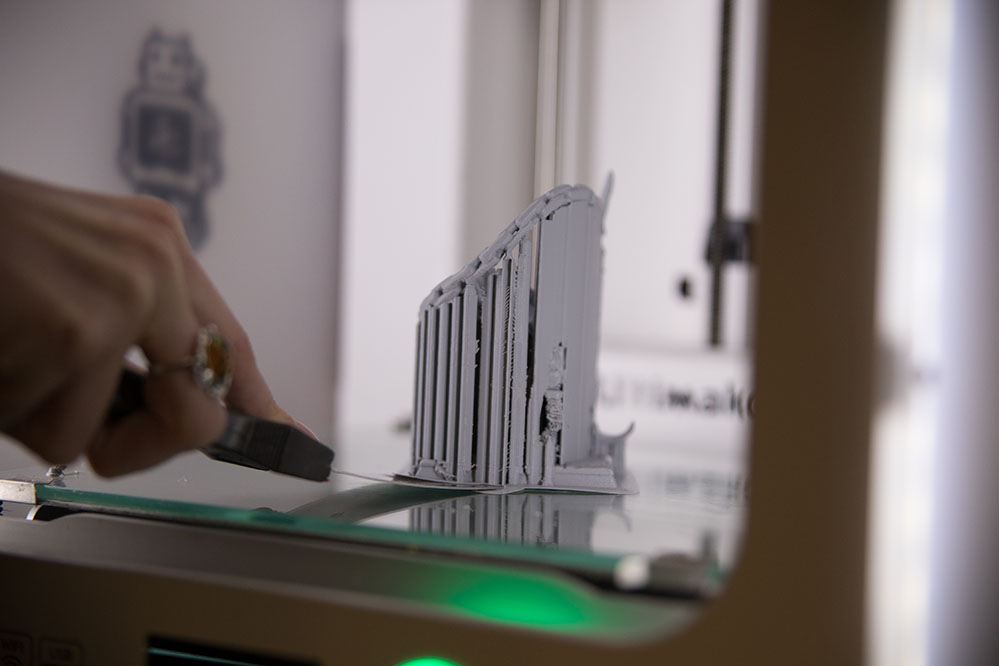

University Libraries at Appalachian State University serves the students, faculty and staff of App State’s Boone and Hickory campuses, contributing to the university’s mission of learning, teaching, advancing knowledge, engagement and effectiveness. Belk Library and Information Commons, the Erneston Music Library and the Hickory Library and Information Commons provide academic resources for all App State students and faculty. Within Belk Library, students and faculty find group and quiet study spaces, digital devices to check out, the Digital Media Studio, the Makerspace, the Virtual Realty Studio, the Special Collections Research Center and more. Learn more at https://library.appstate.edu.

About Appalachian State University

As a premier public institution, Appalachian State University prepares students to lead purposeful lives. App State is one of 17 campuses in the University of North Carolina System, with a national reputation for innovative teaching and opening access to a high-quality, cost-effective education. The university enrolls more than 21,000 students, has a low student-to-faculty ratio and offers more than 150 undergraduate and 80 graduate majors at its Boone and Hickory campuses and through App State Online. Learn more at https://www.appstate.edu.

What do you think?

Share your feedback on this story.