BOONE, N.C. — Year by year, millimeter by millimeter, human footprints made in Africa at the end of the Pleistocene Epoch are slowly vanishing. The 400 or so footprints, located near a site known as Engare Sero in Northern Tanzania, represent the largest assemblage of ancient human footprints in Africa.

The prints were discovered around 2006 by a native of Engare Sero and brought to the attention of Dr. Cynthia Liutkus-Pierce, professor in the Department of Geological and Environmental Sciences and director of the environmental science program at Appalachian State University, in 2008. Her collaborative research on the age and formation of the footprints was featured in National Geographic and The Washington Post. She determined the footprints are between 19,000 and 10,000 years old.

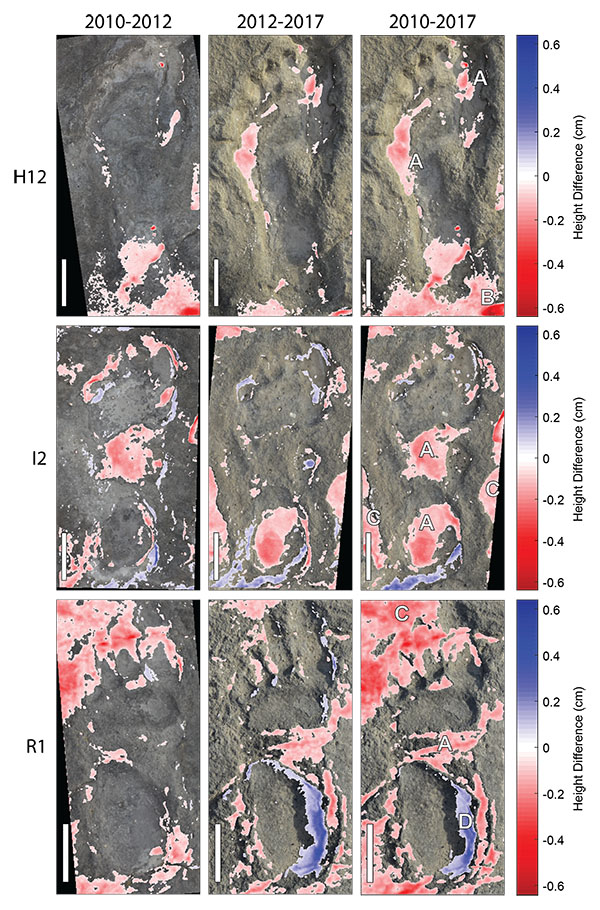

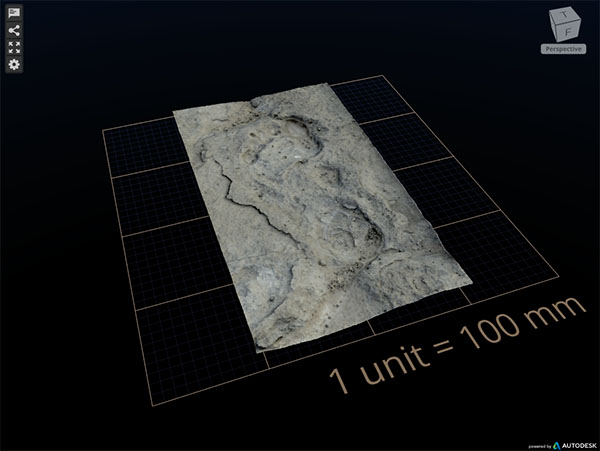

A study published Aug. 21 in Quaternary Science Reviews led by Appalachian researchers Brian Zimmer, Liutkus-Pierce and Dr. Scott Marshall has quantified the erosion at the Engare Sero footprint site using photogrammetry and point cloud comparison algorithms. Zimmer and Marshall are senior lecturer and associate professor, respectively, in Appalachian’s Department of Geological and Environmental Sciences.

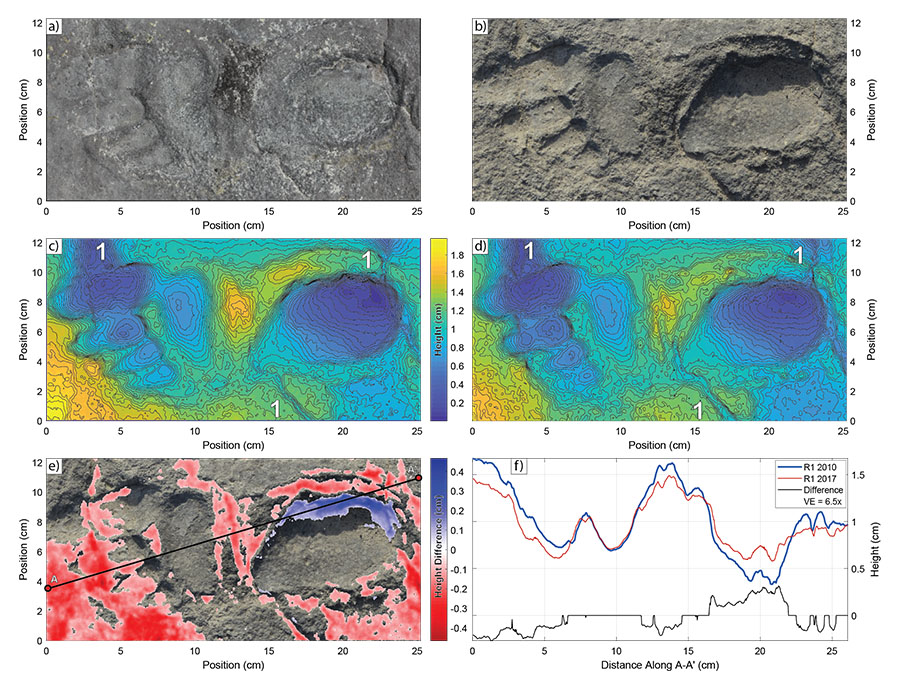

This set of images details one footprint found at the Engare Sero site in Northern Tanzania, Africa. The top row shows pictures of the footprint in 2010 and 2017, and the middle row shows digital elevation models for each print. The bottom row, left, shows where erosion occurred (in red), and, right, is a cross section showing the original profile of the footprint in blue and the eroded profile in red. Figure courtesy of Scott Marshall

Research for the article, titled “Using differential structure-from-motion photogrammetry to quantify erosion at the Engare Sero footprint site, Tanzania,” was a collaboration between Appalachian, Chatham University and the Smithsonian Institution. The researchers concluded that the prints at Engare Sero experienced average rates of erosion, ranging from 0.10 to 0.17 millimeters per year over the seven years of the study.

That may sound like a small amount, but the team has seen the effects of that erosion. Zimmer, first author of the research article, said, “Already, several prints identified in 2010 were impossible to find in 2017.”

Footprints tell a story

The footprints tell a valuable story, because unlike fossils of bones or teeth, footprints disclose information about the activity and behavior of the print maker, Liutkus-Pierce said.

“From the size, shape and arrangement of the footprints, we can tell how many individuals were in this group, whether they were men or women, adults or children, and whether they were walking or running, and moving in a group or individually,” she explained. “For the nonscientist, this is a pretty incredible site that preserves an incredible glimpse into human prehistory.”

Through her research, Liutkus-Pierce concluded the footprints were made by a group of more than 20 individuals — mostly adult women, with a few children and a couple of adult men.

“Two of the individuals are running, and there seems to be two groups walking in different directions at different times,” she explained. “For example, this looks similar to foraging parties of the modern Hadza people in East Africa.”

Liutkus-Pierce said she believes the erosion of the prints isn’t related to climate change. The erosion data are from a seven-year period, which she said she doesn’t think is long enough to attribute to climate change. She said erosion happens naturally, and some footprints erode faster than others.

‘Pretty spectacular science’

According to Liutkus-Pierce, the technique used to calculate the erosion uses data that is very easy to collect in the field — basically, she said, all that is needed is a digital camera to create “pretty spectacular science.”

“Others in the research community think you can only get high-resolution data like this from laser scanning,” she said, “but Brian and Scott have shown that with simple photographs and some data processing, we can get incredible detail.”

The research has broader implications in the field of paleoanthropology.

Paleoanthropologists use data on footprints — size, length, depth — to calculate the body size of the individual who made the footprint. This research shows that even over the course of a few years, the length and/or depth of the footprint can change, which would affect any interpretations of the size, height and weight of the person who made the tracks.

Liutkus-Piece added, “This doesn’t just mean human footprints either — there is a huge research community who work on dinosaur footprints, and this has implications for them as well.”

According to Zimmer, the technique can be applied to more than just erosion.

“In addition to monitoring for erosion, this technique can also be applied to other types of change over time,” Zimmer said, “such as glacial advances and retreats, changes in vegetation cover of a landscape or even how a volcano inflates prior to a potential eruption.”

The ancient tracks at Engare Sero have stood the test of time, but they won't last if left exposed to the elements.

About the Department of Geological and Environmental Sciences

Located in Western North Carolina, Appalachian State University provides the perfect setting to study geological and environmental sciences. The Department of Geological and Environmental Sciences provides students with a solid foundation on which to prepare for graduate school or build successful careers as scientists, consultants and secondary education teachers. The department offers six degree options in geology and two degree options in environmental science. Learn more at https://earth.appstate.edu.

About the College of Arts and Sciences

The College of Arts and Sciences (CAS) at Appalachian State University is home to 17 academic departments, two centers and one residential college. These units span the humanities and the social, mathematical and natural sciences. CAS aims to develop a distinctive identity built upon our university's strengths, traditions and locations. The college’s values lie not only in service to the university and local community, but through inspiring, training, educating and sustaining the development of its students as global citizens. More than 6,800 student majors are enrolled in the college. As the college is also largely responsible for implementing App State’s general education curriculum, it is heavily involved in the education of all students at the university, including those pursuing majors in other colleges. Learn more at https://cas.appstate.edu.

About Appalachian State University

As a premier public institution, Appalachian State University prepares students to lead purposeful lives. App State is one of 17 campuses in the University of North Carolina System, with a national reputation for innovative teaching and opening access to a high-quality, cost-effective education. The university enrolls more than 21,000 students, has a low student-to-faculty ratio and offers more than 150 undergraduate and 80 graduate majors at its Boone and Hickory campuses and through App State Online. Learn more at https://www.appstate.edu.

What do you think?

Share your feedback on this story.