Conversations with smart people about stuff that affects our world, and how we affect it

Hear Jon Ronson on the phenomenon of public shaming via social media. Have we come that far from the stocks in the public square? Is Twitter our new scarlet letter?

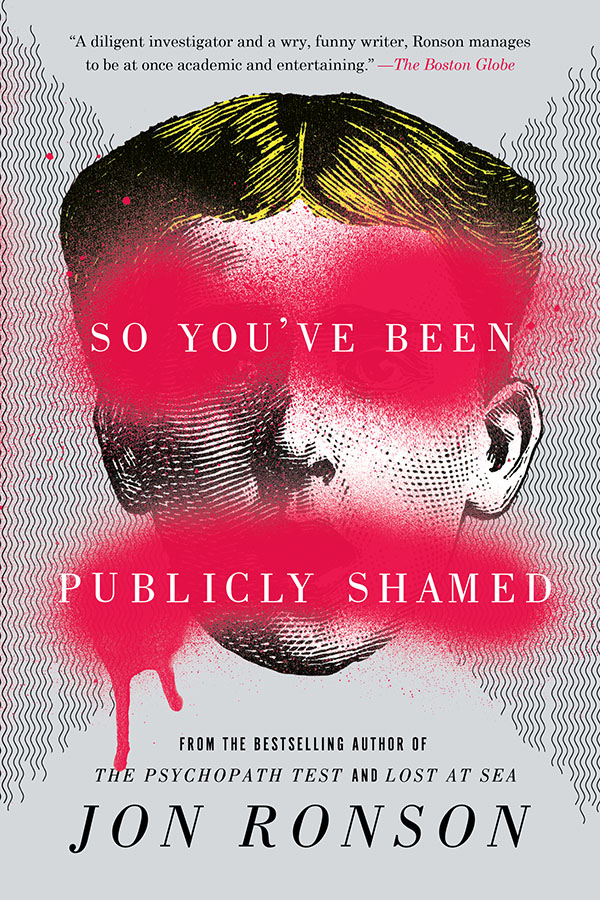

Ronson’s book “So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed” was the 2016 selection for Appalachian State University’s Common Reading Program. Since 1997, incoming students have been asked to read a book to establish a common experience with other new students that will help develop a sense of community and introduce them to academic life at Appalachian.

Hi SoundAffect listeners - during the course of this conversation, you will hear a couple of words you might find objectionable. If you would prefer not to be surprised by them while listening, you can read the transcript below, where you can see the words and the context in which they were used.

Hear Jon Ronson on the phenomenon of public shaming via social media. Have we come that far from the stocks in the public square? Is Twitter our new scarlet letter?

Transcript

Megan Hayes: Jon Ronson is an award winning author, documentary maker and screenwriter. He is the author of nine books including the best selling “The Psychopath Test,” “The Men Who Stare at Goats,” “Them Adventures with Extremists” and “Frank: The True Story That Inspired the Movie” He is a regular contributor to the public radio show “This American Life” and has written for the British national daily newspaper The Guardian as well as for GQ and The New York Times. His TED talk “When online shaming spirals out of control,” has been viewed nearly 1.5 million times.

His latest book, "So You've Been Publicly Shamed," explores the phenomenon of public shaming, including people who have been shamed, those who have done the shaming, including Ronson himself, and ultimately the journey he took from viewing shaming as a freeing, democratizing process to viewing it as a process that reduces our society to one that is intolerant, and unaccepting of the complexities of what it means to be human.

Jon Ronson, welcome to Appalachian, and welcome to SoundAffect.

Jon Ronson: Thank you Megan! It’s very nice to be here. I should point out that 1.5 Million Ted Talk views is actually quite bad. It’s quite disappointing. My other Ted Talk on The Psychopath Test has something like 7 million views. It saddens me because it makes me think that people love to demonize others so they want to see talks about psychopaths because we love nothing more than to declare other people insane whereas talks about humanizing other people are just less popular.

MH: You don’t think people are just afraid they are psychopaths?

JR: Well there is some of that. There is a paragraph in the book that I didn’t think was a stand out paragraph at all where I quote somebody as saying that if you’re reading this book and you’re worried that you may be a psychopath, that means you’re not one because psychopaths never worry about being psychopaths it’s like a great feeling to be a psychopath. People would say, “Oh I was so nervous I was reading your book thinking I might be a psychopath and I was so nervous but I was so pleased when I came to that bit that said I’m not one.” I was thinking, “My God are there hundreds of thousands of people out there who on the scantiest of evidence think they are psychopaths. I have never thought I was a psychopath. But then again I have an anxiety disorder and it’s impossible to be a psychopath and have one.

MH: I think you’re probably just more informed than the rest of us. We worry whenever we do something wrong that we might be a psychopath.

JR: I guess so. I just pictured when you said that…an anxious psychopath. That would be a terrible thing to be. You know you have an anxiety spurt and it manifests itself and you just kind of instinctively start murdering. What a terrible combination that would be.

MH: Well if I could take this in a slightly different direction what I wanted to mention was there some who might listen to this who haven’t read the book, “"So You've Been Publicly Shamed.” You spent three years delving into the repercussions of people who dared to be bold. Whether they were making a joke or saying something uninformed and not very well thought out on social media before you published the book in 2015. I was thinking while I was reading it…this could just be me ...but I feel like this is even more commonplace now than it was. Do you think that’s true?

JR: Yes. I think it’s true. I think it’s gotten worse since my book came out. It’s funny the New York Times…the way that my book sort of made it into the world first was that the New York Times ran an excerpt about this woman named Justine Sacco who was about to get on a plane to Cape Town and she tweeted, “Going to Africa. Hope I don’t get aids. Just kidding. I’m white.” While she was asleep on the plane, Twitter dismantled her life. It was never the same again. So that was the story that the New York Times ran for my book. The story was very passionately like we were wrong to do what we did to Justine Sacco for many reasons. Not least of which that she was asleep on a plane and completely oblivious to her destruction and had no opportunity to explain her joke which was actually an attempt at a liberal joke. So when it came out people were writing editorials that said this story would stop shaming. That it would put a halt to a culture of shaming. Really it didn’t. Things just got worse and more bloodthirsty. Sometimes more deserved than others. Sometimes horrendously undeserved. There is one going on at the moment that started like two days ago. It was kind of deserved. So since it was deserved and the person did a reprehensible thing the ferocity of the violence is worse than I think I’ve ever seen. It’s a guy called Nico Hines. He is a British Journalist who was at the Olympics and wrote an article for The Daily Beast. I never read it so I’m at a position of ignorance here but he was trying to write a funny article about Grindr in Rio and he ended up outing gay athletes including gay athletes who come from countries where when they are outed they can be murdered. So it was a terrible thing that he did even if he wasn’t conscious of what he was doing. What is really interesting is because there is little ambiguity to how bad his thing was, the shaming is extraordinary. I’ve never seen such a bloodthirsty shaming. I had a look at it the other day and the last time it was like, “Slit your wrists.” That was the first one that I saw. Of course because I wrote the book on public shaming, every time something like this happens, people that didn’t like the book say, “Oh I’m looking forward to hearing Jon Ronson cape up for Nico Hines.” they think that because I wrote a book that’s against disproportionate public shaming that also must mean that I’m in favor of outing gay athletes. Anyway there is some really violent language with this shaming and what that makes me feel is that shaming is always about more than the transgressions. Surely we can discuss even the Nico Hines shaming in nuanced terms without that meaning that we are in favor of what he did. Shamings are always about more than just the transgressions.

MH: That brings me to a question that I was going to ask you later. You met several people who lost their jobs as a result of the public response to them being culturally insensitive on social media.

JR: Yeah and things way less bad than what Nico Hines did. I was interested in writing about people who were disproportionately punished and misinterpreted. I wanted the book to be about the disproportionate punishment of people who really hadn’t done very much wrong at all.

MH: Do do you think employers have a role in this to step in and say, “Okay, so maybe this doesn’t line up with what we believe as a corporate entity but this is a human being and as a human we’re going to say that we’re going to work with them maybe they need sensitivity training or maybe we’re just going to agree that they are human and that they have done all these other great things and so therefore as their employer…” Do you think that could stop some of this?

JR: When that happens I am delighted because there is an obligation to stand up to abuse of power. And abuse of power happens on social media too even when it’s being done by nice people like us. What I noticed was that, you know I’ve written about abuse of power lots of times in my career and the only time I have ever been criticized for it was when the power being abused was happening on social media. I think it’s incredibly important for companies to stand up and defend where appropriate. This Nico Hines thing that’s unfolding right now was a really stupid thing. That should not have passed through all the levels and ended up on the daily beast site. But when somebody just tells a joke and it comes out badly and is fired out of fear…when Justine Sacco was fired for that joke what was going on there was fear and corporate damage limitation.

MH: Yeah they had tweeted before she even got off the plane.

JR: They basically implied that they were going to fire her before she got of the plane and then fired her as soon as she even got off the plane. I didn’t use this in the book but she told me that they made things worse. They tweeted, “Employee in question currently unreachable on an international flight.” That turned the rage into excitement. The fact that she was on a plane and didn’t know this was happening was hilarious to people. They made it worse and then they fired her. Her company was IAC the media company that runs Ok Cupid and possibly The Daily Beast…I could be wrong about that though. This could be IAC’s second major shaming. It’s run by Barry Diller. Chelsea Clinton is on the board of directors. You don’t need to dig into a powerful corporation very far before you find Chelsea Clinton.

MH: Do you think ultimately power is what the shamer is seeking?

JR: It’s quite often a misplaced sense of empathy. I mean the desire to be empathetic is what leads people to do these incredibly unempathetic things. So compassion and empathy quite often is propelling people to do these uncompassionate acts. It’s partly because…I talked about this this morning when I gave the convocation speech. I wrote a new speech for the convocation because I thought to myself, “My God it’s going to be like 3500 students there that I could either inspire or accidentally disincentivize them. I have disincentivized young people in the past so I didn’t want to do that so I wrote a whole new speech and I was really thinking about it and I thought that we had created this kind of utopian world where we were no longer misogynists. We weren’t racists. We were compassionate to people with mental health issues. This was a great world that we had created. But we kind of just fell in love with it so much that it turned us. I guess it’s the old utopia dystopia thing. It was like we fell in love with our awesomeness. It was like we had awesomely created this compassionate, shaming, non-racist, non-misogynistic and non-homophobic world. We were so in love with it that when somebody got in the way our response was furious. I understand that impulse. I was part of that. I was an early adopter of Twitter. I loved this happening. I thought it was incredible. I remember a friend of mine, Graham Linehan said, “The internet is black magic but Twitter is white magic.” It felt like we were creating a brave new world and then when we realized that we could do something about bad people we did it with a fury. It started off being corporations. I remember a big early shaming was L.A. Fitness a gym company. There was a heavily pregnant woman who couldn’t afford the fees and L.A. Fitness refused to cancel her membership. Twitter got them to change their mind. We shamed them into changing their mind. We were like, “Whoa! This is amazing!” That quickly turned into ruining private individuals who had done almost nothing wrong.

MH: Yeah so do you think the role of the internet troll has value?

JR: I don’t want to write a book about trolls because trolls enjoy chaos. Personally I was much more interested in writing about people who saw themselves as good people. Trolls know they’re dicks by and large. They enjoy it. Whereas the people who destroyed Justine Sacco, there was a few trolls among them but most of the people who destroyed Justine were good people who then by the way reacted furiously when I wrote a piece defending Justine Sacco.

MH: Their rage was violent rage.

JR: Violent rage against her…they said, “Rape her murder her.”

MH: That doesn’t sound like good people.

JR: The good people were the ones who were tweeting “In the light of Justine Sacco's horrendous tweet, I am donating to aid for Africa.” They were the good people. So there were a lot of compassionate people, then came trolls saying, “Somebody HIV positive should rape this bitch and then we’ll find out if her skin color protects her from AIDS.” That was one tweet…So then there were the “rape and kill her” tweets. Then there were scores of hipsters. Hipsters loved it. Funnily enough it’s the hipsters that are my least favorite ingredient in all of this.

MH: Why is that?

JR: I don’t know. There is something especially annoying about the emptiness of it. Yeah the emptiness.

MH: You know, one of the things that struck me in your book was how many times you’d meet someone who seemed on the surface to have done something really abhorrent and they were exposed, you went and you met them, and once you started talking to them, there were several times in your book where you said, “I actually really liked this person.”

JR: Yeah, you tend to like people when you meet them. I mean, unless they’re monsters. You know, I’ve been doing this for thirty years, so I have met a few monsters…most people aren’t monsters. As somebody says to me in the book, you know, when you look under the hood, most of us aren’t Voldemort. Most of us are just kind of messed up. We’re good and we’re bad, and good and bad. I do good work and I make mistakes. You know, I’m a good father and then sometimes I do something stupid, and that’s how most of us are. And I think that’s a much healthier way to perceive our fellow human beings, is like a mess. But Twitter promotes conflict. Twitter promotes, you know, drama. A stage for constant, artificial high dramas, and I think it’s going beyond Twitter now. I think it’s what explains this, you know, messed up election cycle. It’s like the atmosphere that starts on social media has now infiltrated mainstream politics. It infiltrates college campuses, the mainstream media. You know, everything is now more heightened because of Twitter. I mean, I hope that’s not a too overblown thing to say, but I don’t think it is.

MH: Well I think it’s interesting you’re talking about Twitter in particular because I do think a lot of us, and I don’t know, maybe it’s because I’m middle aged, but I feel like there’s this tendency for my generation to blame a lot of the collateral damage of public shaming on technology. And I think technology does allow us to take this more one-dimensional approach, for sure, than when we’re having this, like you said, face-to-face conversations and you get to know someone and really understand that they’re human and there is a humanity we have in common. But I think at least one person that you interviewed for your book points out that this shaming phenomenon is not new.

JR: The shaming phenomenon isn't new, but I think elements of it are new because of technology. Firstly, I believe that, you know, I spent some time up at the Massachusetts archives trying to work out why public shaming had died out in the 1840s, 1850s and I didn’t find a single document, I mean they may exist, but I didn’t find a single document that said we have to stop public shaming because it’s ineffectual. A shamed person can just lose themselves in the crowd, you know, now that we live in cities and not villages. Which I think is a common perception about why public shaming died out. But what I did find was a lot of documents that were like we’ve got to stop public shaming because it’s barbaric. It’s turning the crowd crazy. It’s disproportionate. And I found lots of documents that said that. So that seems to be why public shaming was phased out in the 1850s. I think technology, to a larger extent, is responsible, mainly because Twitter promotes…Twitter in particular, I think, promotes a kind of echo chamber where we surround ourselves with people who feel the same way that we do and we kind of approve each other.

MH: Right.

JR: And I think you notice that on a daily basis. When you look at a Twitter feed…let’s say someone says something and then you look at the replies, they tend to all agree with each other.

MH: Like living in a gated community.

JR: Yeah it is! Like if somebody says “I love Megan’s podcast,” all the comments underneath will say, “Yeah I love Megan’s podcast too! Yeah, I think it’s a really great podcast.” But then if somebody tweets, “I really don’t like Megan’s podcast,” then all the tweets underneath will be, “No, nor do I.” So it’s an echo chamber, and an echo chamber will promote fury, a destabilizing factor. I think that’s one reason. I think algorithms have got a part to play in it too. Algorithms give us back our nastiest selves. I’ve become really interested in this lately. So for instance, take porn. I’m doing a series at the moment for Audible which is partly about the porn industry, and I’ve been looking at porn algorithms, and basically what gets to the top is the kind of nastiest stuff. Like boring old vanilla porn, which is how porn was in the eighties and nineties, is on page five of Google now. You know, it’s the most vicious. So basically, algorithms feed us back our darkest impulses.

MH: Wow.

JR: Yeah, I’m really interested in that.

MH: You know the examples of public shaming and redemption you explore in your book are either American or British. Do you think that this is a cultural phenomenon that’s particular to our societies or do you think shaming’s something that humans share across cultures?

JR: You know, I don’t know the answer to that question. When I first moved to New York four years ago this month, I noticed a lot of the shamings that were happening were happening in New York, and I became really interested in that, and I just got consumed with that. And as a result, I never went…you know, in some of my other books I go to far away places. So in them I end up in Cameroon, and other things like that, but in this book I just stuck to Britain and America really. Once in awhile I get an email from somebody…just the other day I got an email from a guy in Hong Kong who’d been publically shamed. He’s an oboist, and he was publically shamed for writing a review about oboes, and apparently became a huge deal in the oboe. And that’s happening in Hong Kong.

MH: Interesting.

JR: Yeah, so really I’m ignorant to question. I don’t know the answer.

MH: There’s a quote in your book that stuck with me. You said, “We know that people are complicated and have a mixture of flaws and talents and sins. So why do we pretend we don’t know this?” So several months out from writing the book now, do you have a theory on why we’re willing to accept the complexities in ourselves but not necessarily in people that we…

JR: I think a lot of it has to do with this kind of…with the way social media promotes high drama. But of course it happens…it doesn’t just happen in social media. It happens in the mainstream media. I’m writing about this, at the moment, actually I went to the RNC. I’m going to write a big nonfiction piece for Amazon. It’s going to go straight onto Amazon about the RNC. And, by and large, the RNC was quite boring. Everybody thought there was going to be violence and there wasn’t any violence. And it was really interesting to see how disappointed everybody was by the lack of outrage and drama. I’ll tell you a story, I’m going to use this in my thing, but I’ll tell you this story. There was a…word got around, I think on day three, that there was going to be a flag burning…

MH: This is the Republican National Convention?

JR: Yeah. I got an email saying there’s going to be a flag burning at four pm. I said “Oh good.” So I went to the flag burning and there was like two hundred journalists or more that had descended upon this flag burning. And a guy turned up with a flag and everyone surrounded him straight away, going, “You’re going to burn the flag!”…and he was like, “No, I’m a Marine!” And he got very upset, “I’m not going to burn this flag. I love the flag!” And then the actual flag burner turned up, who was like an anarchist, and was surrounded by two hundred people, two hundred journalists. It was like one flag burner, two hundred journalists…I’ve never seen such a frenzy. As a result of all the pushing and shoving of the journalists, when he set fire to the flag he actually set fire to his trousers. And everyone’s going, “Your trousers are on fire, stupid!” And so he ended up in the hospital, and then there was such a kind of…everybody was like “AAAHH!”…that a kind of, I’d go too far to say riot, but it got violent. And then they slammed closed the doors of the convention, and I was trapped between this commotion with fire, and a man’s trousers on fire, and two hundred journalists trying to get a shot of the guy on fire, and then the door was slammed so me and a bunch of Republican delegates and a few other journalists. You know, people from TED Talks and stuff, were all trapped between the commotion, and the cops weren’t letting us in because it was getting violent. It nearly got dangerous, and it was all because of the journalists. It had nothing to do with reality. And that really interested me, you know, our need for drama. We seem to be living in times of heightened need for drama, both on social media, and in mainstream politics, and in mainstream media, and that’s the subject I think of this story I’m writing for Amazon.

MH: You know I’d love to think that Appalachian’s university community could come together in a social media setting and take a stand and say we’re going to use this venue to treat each other decently. I think that’s a lot of what they were setting the stage for at the event you were at earlier today.

JR: There was a lot of talk of compassion, curiosity, open-mindedness, and I wonder where the …obviously something that has been happening over the last couple of years at certain college campuses is things have gotten a bit like social media. Things have gotten quite combative. With all this stuff about safe spaces and trigger warnings, and I have very mixed feelings about those subjects, and it did make me wonder whether there was a deliberate attempt here to say let’s not turn this campus into that. Let’s keep it a place of open-mindedness and friendliness and compassion and it’s much better to learn from each other through friendly dialogue than through hostility.

MH: Yeah, that is definitely part of what’s happening, is there are some faculty and staff who are saying, you know, we can mentor people into seeing the humanity in one another, and going beyond that one-dimensional dialogue. That one-dimensional way of looking at people, I guess.

JR: But I’m very glad that they asked me to the Convocation address because that’s my thing too.

MH: Yeah.

JR: Which doesn’t mean, by the way, I don’t like it either when there’s this kind of blanket “anybody believes in safe spaces and trigger warnings, they’re just like…idiots!” Like I don’t believe that, because people get triggered. Like I’ve been with Monica Lewinsky lately, and here’s somebody who, you know, suffered some PTSD and gets triggered. People do get triggered. Like everything, I’m just a boring liberal that can see both sides, but on balance I would say that a college that becomes too into safe spaces and trigger warnings and so on is going down a wrong path.

MH: Do you think that there is the potential to really sway social media with the community like this?

JR: You know, I think it’s just a matter of personal responsibility. Just don’t do it…yourself. Even someone like Nico Hines…Nico Hines is the big shaming of this past week or so…he obviously did something very stupid. My guess is that it wasn’t…he wasn’t being deliberately evil. Not many people are deliberately evil, you know, he made a mistake and he got sort of swept up in his own hilarity is my guess. But even with that I’m thinking, “You know what? Not everybody has to…just because voiceless people now have a voice doesn’t mean you have to constantly use your voice all the time!”

MH: That’s what I tell my nine-year old.

JR: You don’t have to…it’s not your duty to pile in on Nico Hines or pile in on who have done things not as bad as Nico Hines. You know we don’t have to do it. You can use Twitter to be silly and funny, or you can use Twitter to be curious and empathetic. And I just think it’s a personal responsibility of people to just try and do that.

MH: Well, Jon Ronson, it’s been a pleasure to speak with you today. Hearing your public speech this morning was really really…it was a treat. It was a treat for our campus and I think that you have a lot to teach our campus. And I appreciate you being here because my hope is that by recording this conversation; we will be able to keep those conversations going beyond your visit here on our campus.

JR: Thank you, and I really enjoyed being here. I’m very glad to have been asked, and thank you for doing this.

MH: Thank you.

JR: Thank you.

Hear Jon Ronson on the phenomenon of public shaming via social media. Have we come that far from the stocks in the public square? Is Twitter our new scarlet letter?

What do you think?

Share your feedback on this story.

Conversations with smart people about stuff that affects our world, and how we affect it

About the Common Reading Program at Appalachian

Since 1997, incoming first-year students at Appalachian State University have been asked to read a book as part of their orientation to the university. By participating in the Common Reading Program, students establish a common experience with other new students that will help develop a sense of community with their new environment and introduce them to a part of the academic life they are beginning at Appalachian. This program is an exciting facet in Appalachian's orientation of new students to life on campus. Learn more at https://commonreading.appstate.edu/about.

About Appalachian State University

As a premier public institution, Appalachian State University prepares students to lead purposeful lives. App State is one of 17 campuses in the University of North Carolina System, with a national reputation for innovative teaching and opening access to a high-quality, cost-effective education. The university enrolls more than 21,000 students, has a low student-to-faculty ratio and offers more than 150 undergraduate and 80 graduate majors at its Boone and Hickory campuses and through App State Online. Learn more at https://www.appstate.edu.

![The Search for Vertical Grasslands [alumni featured]](/_images/_posts/2026/03/vertical-grasslands-600x400.jpg)

![How NCInnovation Is Rethinking Economic Development in North Carolina [faculty featured]](/_images/_posts/2026/02/rethinking-economic-development-600x400.jpg)