BOONE, N.C. — The protest of the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL), led by citizens of the Standing Rock Lakota Sioux Tribe, presented Appalachian State University assistant professor of anthropology Dr. Dana Powell with an unexpected opportunity to further her research around indigenous land claims and energy infrastructure and enhance her teaching. The DAPL, also known at the Bakken Pipeline, is a 1,170-mile, $3.8 billion project led by Energy Transfer Partners, carrying crude oil from the Bakken shale fields in North Dakota across four states and into Illinois, where it will connect with existing pipelines to transport oil to the Gulf of Mexico.

Powell said personally she hoped the outcome at Standing Rock would include a victory for tribal members and their allies, and on one level it has. The United States Army Corps of Engineers decided Dec. 4 to block, for now, the building of an oil pipeline near the reservation.

The ongoing conflict in North Dakota and Powell’s work, however, likely will continue on for years to come. There is much more at stake, she said, than stopping this one pipeline: “Rural North Dakota is a global site of action in the transnational energy business.”

“This is about climate change and human and non-human life in the anthropocene. These are the big questions that inform this research project. Politically, this is about Native sovereignty over territory, and if people don’t understand that, they haven’t done their homework... There are deeper levels of understanding and they are historically deep and culturally diverse … reaching beyond Standing Rock, affecting energy-rich Native and First Nations across North America.

“You cannot talk about sustainability in the United States if you don’t deal with the question of Native sovereignty. The ‘3Es of sustainability’ that folks like to reference [environment, economy and equity] do not speak to what’s at stake with indigenous land claims. That can’t fall under equity. The very existence of these nations and the way in which the Sioux can make a claim poses a fundamental challenge to the federal government of the United States,” she said.

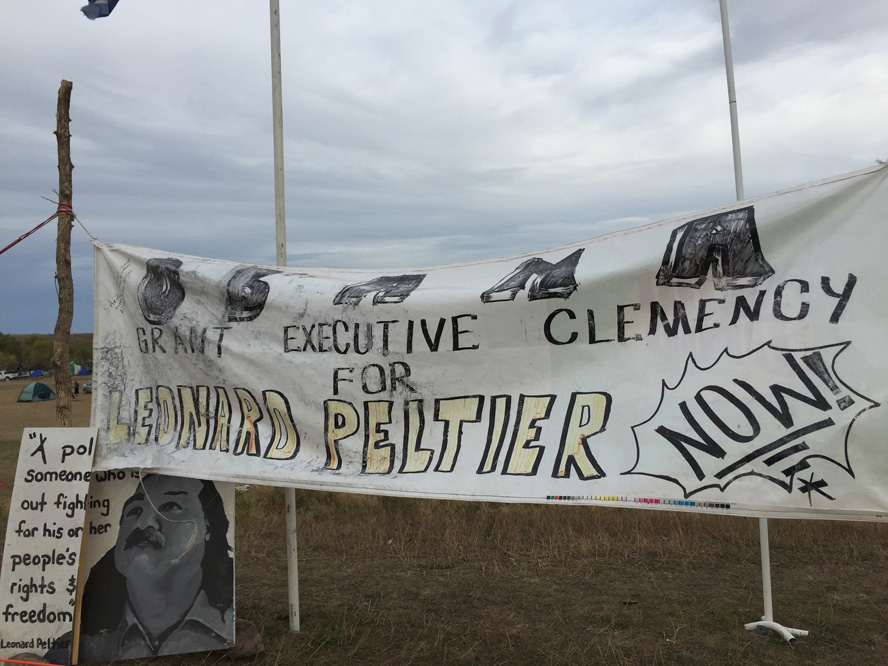

The researchers saw banners, T-shirts, posters and flags along the fence line that runs beside Highway 1806. They were displayed by different Native nation groups and other visitors, including NGOs, veterans and schools groups in an act of support for the water protectors. Photos by Dr. Dana Powell

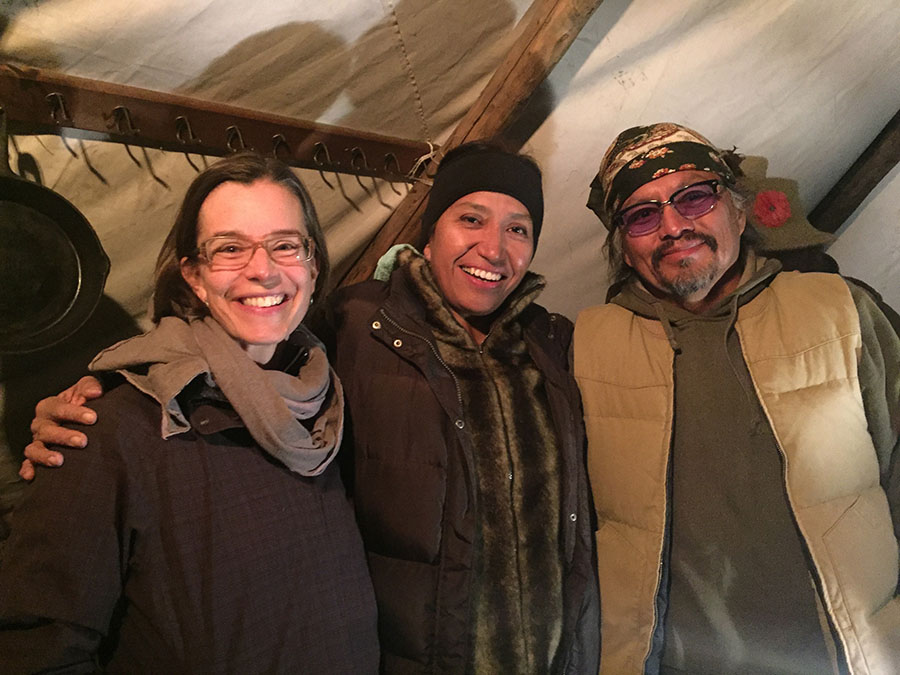

At the invitation of associates from the Diné (Navajo) Nation, with whom Powell has worked since 2000, and who were going to North Dakota in a show of support for the Standing Rock struggle, Powell and her undergraduate research assistant, Ricki Draper ’18, traveled to the site in late October, interacting with people on the ground in the Oceti Sakowin (Seven Council Fires/The Great Sioux Nation) camp. Powell returned again over Thanksgiving for additional research.

Beginning in February 2016, members of the local Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and ultimately thousands of Native American and non-Native supporters set up camps along the Cannonball and Missouri Rivers, about an hour south of Bismarck, North Dakota, in protest over the proposed DAPL. As “water protectors” (rather than “protestors”), activists criticized the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for allowing Energy Transfer Partners to bring the pipeline through what is historically Sioux territory (and was officially part of reservation territory until claimed by the Army Corps in the early 1950s), threatening the Missouri River, the longest river in North America. The river is the tribe’s source of drinking water, and also supplies millions downstream. Opponents of DAPL said the project threatened sacred native lands including burial sites and could contaminate their water supply from the Missouri River were it to pass under the river’s Lake Oahe, as proposed.

Powell, who joined the Department of Anthropology in 2011, had done extensive ethnographic fieldwork in the Diné (Navajo) Nation in the U.S. Southwest, as well as some related work in Chiapas, Mexico, focusing on indigenous movements and energy technologies, both fossil fuel-based and renewables.

‘Standing Rock kind of happened to us’

The eruption of conflict at Standing Rock this year presented an unexpected opportunity for fieldwork that was immediate, compelling and intimately related to her longstanding work with Diné colleagues, Powell said. She was granted her second University Research Council (URC) award last year, to continue her research around environmental justice, indigenous territories, energy infrastructure and public debates on technology in the Navajo Nation. She had planned to return to Navajo territory in fall 2016, for preparatory work to help launch a new project there, following on her coal plant research. Also in the works was a proposal to collaborate with a Maori colleague in New Zealand around water rights, electricity and Maori territory. But, by the end of August, the friction at Standing Rock was escalating and her Diné friends invited her to join them in North Dakota.

“Standing Rock kind of happened to us,” she said. Normally, cultural anthropology research projects take long-term planning and preparation, including a fair amount of paperwork for institutional review board approvals. However, the National Science Foundation (NSF) now has “what they call a rapid response situation for funding in emergent and unanticipated contexts and the URC seemed to understand that,” she said. “And so did the IRB (Institutional Review Board). They enabled me to respond quickly and flexibly to the emerging situation.”

Powell said she was able to use her URC award and funds from the Office of Student Research allocated for Draper’s undergraduate research assistantship to launch this project. “I am so grateful for the support from the university and from my department ... in understanding the significance and the urgency of this kind of work,” she said, “especially when it falls during a regular semester of teaching.”

In each of her fall anthropology courses, Powell brought the issues at Standing Rock into the classroom for discussion on how issues of culture, technology and power impact local communities. In her course Native America through Ethnography, she taught the course from the field for one class meeting, talking with students via Skype from the Oceti Sakowin camp. In this course and her other upper-level course, Anthropology of Environmental Justice, she assigned readings related to the Standing Rock issue and was able to integrate it as a case study into class discussions, drawing upon both of her fieldwork trips to North Dakota. Standing Rock will also inform her spring course titled Political Ecology and Sustainability.

All photos by Dr. Dana Powell, professor of anthropology at Appalachian State University

At the encampment

In mid-October, Draper and Powell flew to North Dakota. Draper is 25 years old, a non-traditional student with five years of experience as a social activist, working on water-related crises and extractive industry impacts. The Greensboro native worked in the Appalachia region, mostly concerned with issues around fossil fuels, before coming to the university. She had planned to study mapping through the Department of Geography and Planning, but after taking a class in cultural anthropology with Dr. Tim Smith, she changed her major to anthropology with a social practice and sustainability concentration. “I recognized I can be a better organizer, a more effective social activist if I develop a more critical analysis of social change through my study in the anthropology department,” she said.

“I wouldn’t have taken any other student along,” Powell said. “[Standing Rock] is not a place for a student who’s cutting her teeth on high-intensity social movements, or an over-eager budding anthropologist. [Draper] is an adult with an understanding of the deep complexities and potential dangers of the situation. She has the background she needs and has the skills and frame of mind to do this kind of fieldwork.”

At the Oceti Sakowin encampment, Powell and Draper camped with Powell’s colleagues from the Southwest, including members of the group Diné CARE (Citizens Against Ruining our Environment). Draper also had contacts of her own there on the ground, enabling her to reach other networks of social practice and critique. Their research methodology was to observe, as activist researchers and ethnographers, by embedding themselves with water protectors and by conducting interviews and audio and visual recordings where permitted.

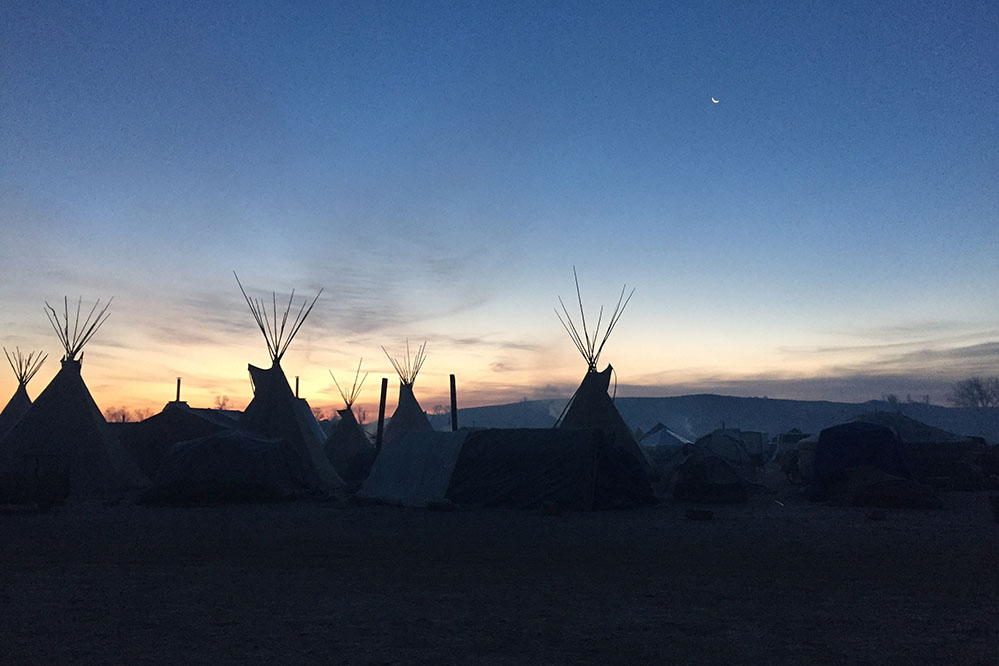

Tarpees at Camp Southwest, one of the named camps within the larger Oceti Sakowin, where Powell stayed over Thanksgiving. The tarpees are made of tarp as opposed to the natural skins of the tipis, are manufactured and have a pre-fabricated opening for a wood stove or oil drum pipe. Photo by Dr. Dana Powell

The professor and student were interested in talking to people who were not regularly in the public eye – as the camps have been teeming with media since September. They were interested in talking with people who had reasons for being there that may not have been so widely articulated, she said. “I want to know what does this mean for the Lakota and regional folks who are leading the encampment, but also for other Native and non-Native people who have quit their jobs, or taken weeks off work… to wash dishes, construct tipis, make art and engage in nonviolent direct action, to build power within the camps.”

The media were everywhere, according to Draper. “[The water protectors] are used to saying: ‘We’re here to protect the water’; ‘We’re here for our children’; ‘We are here to fight for indigenous sovereignty.’ Those are all real and truthful, but we are working to get the personal story beyond the talking points,” she said.

To do that, Powell explained, “We are doing what we call participant observation. We are trying to unsettle, swerve or push past the prepared statements. We recognize and hear those talking points, particularly from people used to being interviewed for immediate publication. There’s a deluge of self-reporting and social media representation on this issue. But this is a very diverse set of water protectors, some of whom are very skilled at messaging, at interfacing with the media and delivering curated responses. We are trying to ask different questions, to tap into oral histories, memories, meanings and related struggles. We are also paying attention to practices of healing and survival … and the aesthetic techniques of the camps. I’m looking at what people are wearing, the signs and murals around the camp, how they are putting up semi-permanent structures. Our [research] is about what people say, but also what people do and create.”

Draper said this experience was different from other protests in which she has participated. Although she knew some of the allies at the site, and had been with them in other actions, her role this time was two-fold. “I was there to contribute to the movement, yes, but also to do my work,” she said. This role, Powell said, this “hyphenated identity,” is not always an easy one, in practice.

“For scholars who have come out of activist movements, there is an inherent dual tension – being an activist and being a researcher. I would argue, with others, that we can do better scholarship because of this kind of engagement, becoming better contributors to our field than if we were pursuing these kinds of social problems, without that depth of experience and investment. Our critical theory is enhanced by this deep level of commitment. I’m surrounded by colleagues here at App who do similar work, in various modes of critique and action, responding to the urgencies of the moment.”

Draper, who said she conducted about 10 interviews while at the encampment, concurred. “Ethnography can contribute to social movements. I’m learning that. I came back to school after working for five years in Appalachia around issues of coal mining and the economic impact in local communities. This [Standing Rock] is activist research. It is amazing to see a movement through a different lens.”

This is not a party

Draper described the campgrounds as a huge, complex community: communal kitchens, food storage, medical care. “Babies were being born there,” she said. “It’s not a space for settlers to come and ‘experience’ the ‘idealistic,’ ‘sustainable’ life.”

Powell concurred, adding: “There are well-meaning folks there who approach this like it is a festival. I heard someone say, ‘This is a lot like Woodstock.’ As an ethnographer and a scholar, that interests me. I want to talk to that person. But as an active collaborator, it hurts, because it displays a real lack of historical, cultural and political understanding. This is not a party. This is no place to take a Frisbee.”

When Powell returned to the campsite for five days over the Thanksgiving holiday, the number of people on the ground had more than doubled, from 4,000 to nearly 9,000, and the situation had intensified dramatically, following the events of Nov. 20, when law enforcement deployed water cannons, rubber bullets and concussion grenades on activists at the front line. The water protectors, she said, now “were looking at a double-layered threat: they had to prepare for living outside in the harsh winter weather of North Dakota and for the increasing possibility of state-sanctioned violence. The reality on the ground is that people don’t feel afraid, but take very seriously the possibility of another, and perhaps more intense, clash with law enforcement and they want to know how to prepare for that; how to spiritually and psychologically prepare to think through the possibility of safety for themselves and others… There is a lot of emotional and logistical labor that goes into readying for an escalating situation.”

Conducting interviews had grown increasingly difficult, Powell said. People were busy and the cold weather and wind were taking a toll. The three interviews she was able to arrange took place in her rental car with the heater running. But because of the intensity, Powell said she had a much deeper level of participant observation.

Next steps in their research and solidarity

Powell said she hopes to return to Standing Rock in the coming months, “as we see how things play out following the Dec. 4 Army Corps announcement. I have large grants in review to extend my work on the Navajo Nation, and I want to explore how the struggle at Standing Rock impacts energy infrastructure struggles in Navajo territory.”

Draper reports: “Since the beginning of October, a group of students, community members and faculty members have been coming together in Boone to respond to the urgent request to show up in solidarity for the water protectors in Standing Rock. We are organizing solidarity actions and community events to support the struggle for clean water and indigenous sovereignty, while building power in our home to resist harmful extractive industry and systems of power that maintain environmental and cultural degradation.

“We are building leadership and actively engaging members of the community who have not been involved in this sort of work before,” Draper said.

Linda Coutant and Dr. Dana Powell contributed to this story.

What do you think?

Share your feedback on this story.

About the Department of Anthropology

The Department of Anthropology offers a comparative and holistic approach to the study of the human experience. The anthropological perspective provides a broad understanding of the origins as well as the meaning of physical and cultural diversity in the world — past, present and future. Learn more at https://anthro.appstate.edu.

About the College of Arts and Sciences

The College of Arts and Sciences (CAS) at Appalachian State University is home to 17 academic departments, two centers and one residential college. These units span the humanities and the social, mathematical and natural sciences. CAS aims to develop a distinctive identity built upon our university's strengths, traditions and locations. The college’s values lie not only in service to the university and local community, but through inspiring, training, educating and sustaining the development of its students as global citizens. More than 6,800 student majors are enrolled in the college. As the college is also largely responsible for implementing App State’s general education curriculum, it is heavily involved in the education of all students at the university, including those pursuing majors in other colleges. Learn more at https://cas.appstate.edu.

About Appalachian State University

As a premier public institution, Appalachian State University prepares students to lead purposeful lives. App State is one of 17 campuses in the University of North Carolina System, with a national reputation for innovative teaching and opening access to a high-quality, cost-effective education. The university enrolls more than 21,000 students, has a low student-to-faculty ratio and offers more than 150 undergraduate and 80 graduate majors at its Boone and Hickory campuses and through App State Online. Learn more at https://www.appstate.edu.