Conversations with smart people about stuff that affects our world, and how we affect it

Dr. David Pilgrim is a public speaker and leading expert on issues relating to multiculturalism, diversity and race relations. Pilgrim, a Ferris State University distinguished teacher who holds a PhD from the Ohio State University, is an applied sociologist who believes racism can be objectively studied and creatively assailed. He is perhaps best known as the founder and curator of the Jim Crow Museum, a 5,000-piece collection of racist artifacts located at Ferris State University that uses objects of intolerance to teach tolerance.

Transcript

David Pilgrim: ...and I had this thought and it stayed in my head for a few seconds, why am I doing this stuff? Why don’t I just dance? You know - eat, drink, and be merry kind of thing, just ignore this. What the hell is my problem that I’m spending my life, I’m not making this up, I had this thought in my head. Then it passed. I know if you have a race-based incident nationally there’s going to be a two dimensional or three dimensional object created within the week. I know it because we’re still buying those objects. So whether I dance or not, whether I close my eyes to what’s going on, it’s still happening. It’s still going to happen.

Troy Tuttle: From Appalachian State University in Boone NC this is SoundAffect.

Megan Hayes: Dr. David Pilgrim is a public speaker and leading expert on issues relating to multiculturalism, diversity, and race relations. Pilgrim, a Ferris State University distinguished teacher who holds a PhD from the Ohio State University is an applied sociologist who believes racism can be objectively studied and creatively assailed. He has been interviewed by National Public Radio, Time magazine, the British Broadcasting Corporation, and dozens of newspapers, including the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Boston Globe, Chicago Tribune, and Los Angeles Times. He’s also the author of numerous short stories, and has served as a consultant to Hollywood actor and producer, Will Smith, for the UPN television show All of Us.

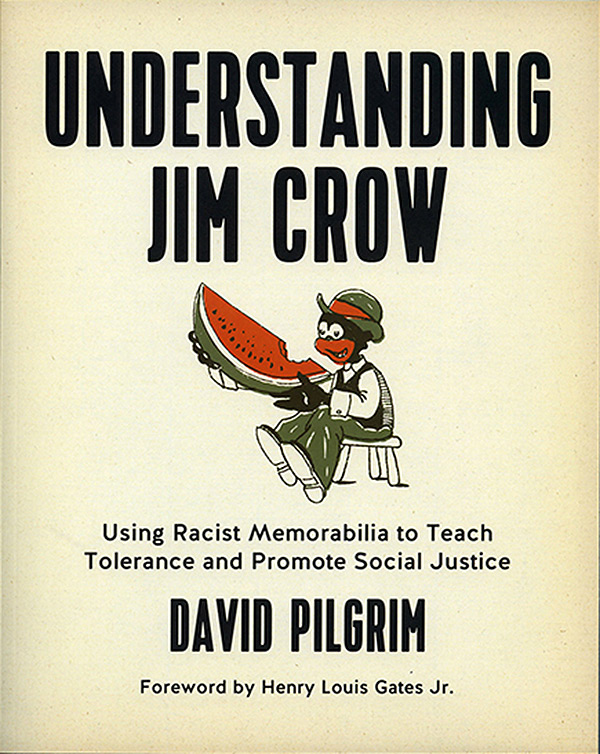

Pilgrim is perhaps best known as the founder and curator of the Jim Crow Museum. A 5,000 piece collection of racist artifacts located at Ferris State University that uses objects of intolerance to teach tolerance. Pilgrim’s writings, many of which are found in the museum’s website, are used by scholars, students, and civil rights workers to better understand historical and contemporary expressions of racism. In 2004, along with Clayton Rye, he produced the documentary, Jim Crow’s Museum, to explain his approach to battling racism. The film won several awards, including best documentary at the 2004 Flint Film Festival. In 2015, Pilgrim’s book, Understanding Jim Crow Using Racist Memorabilia to Teach Tolerance and Promote Social Justice, was published by PM Press.

This week on our campus, Doctor Pilgrim is sharing the exhibition Them, Images of Separation which is on display as part of our university’s series of events, Say What? Examining freedom of speech at App State. Them is a traveling exhibition of the Jim Crow Museum of racist memorabilia, and showcases items from popular culture used to stereotype different groups. The negative imagery found on postcards, license plates, games, souvenirs, and costumes, promoted stereotyping against African-Americans, Asian Americans, Hispanics, Jews, and poor whites, as well as those who are the other, in terms of body type or sexual orientation. Dr. David Pilgrim, welcome to Sound Affect.

DP: Thank you. I’ve enjoyed my stay here at the University, everyone has been very kind, and the discussions have been great.

MH: Good. Your visit to our campus is part of a week long deep dive our campus is taking into the complexities of our country’s first amendment right to free speech, and how we seek to balance that with an awareness of the effects that our expressions of speech, whether they’re words, or actions, or imagery have on others. The exhibition you curated, and which is on display on our campus this week has some very disturbing imagery in it. Can you talk about how the exhibition evolved?

DP: The Jim Crow Museum was founded in the mid-90s. I moved into a larger facility in April 2012. We’re very proud of it, but we recognize that not everyone’s going to make the long trip to the metropolis of Big Rapids, Michigan. So, to deal with that, we decided to create a traveling exhibit. The first one was called Hateful Things. The objects in it came from the museum. When people saw it I sometimes got this response from them, “You say that you are you are concerned about racial justice and social justice, but you only focus on the Jim Crow objects, anti-black objects. Why are you not interested in the oppression of other groups?” My first response, which was kind of flippant was, “But we’re a Jim Crow Museum. Obviously, we would focus on objects related to segregation for example. The more I thought about it, the more I started thinking, you know I’ve seen other objects out there. I think a critical point for me was I reread, and by that I mean really read Dr. King’s letter from Birmingham jail, saw the idea of injustice anywhere being a threat to justice everywhere. It not only resonated with me, I mean it really kicked me in the stomach so I decided, well let’s create a second traveling exhibit. This one, yes, it will still have some pieces from the Jim Crow collection, but it will also show how other groups, you know poor whites, members of the LGBT community, indigenous people or first world people, first nation people. Actually, those mean two very different things, but just other groups. Now, I have to say something right now, which is we did get criticism in addition to the criticism you might expect, which is, oh these things are horrible, they’re terrible, we shouldn't be thinking about this kind of..… We also got criticism from people, I suppose you could say they were on the left, and that criticism was that that traveling exhibit, in some way, would dilute our message. That it at least, indirectly compared the victimization of these other groups with African-Americans. I listened to that, but in the end, I thought it was an important to show that, again, it wasn’t just African-Americans, but that there were other groups who experienced prejudice and discrimination in our culture.

MH: To get to kind of the beginning when you started curating the artifacts for the Jim Crow Museum, you talk in your book, Understanding Jim Crow, about the first time you purchased a racist artifact as a child, and you smashed it on the ground and destroyed it. You know, I imagine that would be most people’s first response to something that’s so viscerally disturbing. What made you decide that you were going to start collecting and preserving these artifacts?

DP: You know, that’s one of the questions I dread most receiving, or most dread receiving.

Speaker 1: I’m so glad I could ask it and just make your life worse.

DP: I just wish I had a better answer. In some ways, I think I was on automatic pilot in those days. I don’t remember the second piece. I don’t remember the third. But I don’t remember a time when I was not collecting. Now keep in mind, this was a long time ago and those pieces were everywhere. They were also in the homes of African-Americans. My aunts, or cousins, or whatever would also have what today would be considered a racially offensive, if not racist piece. So I’m just not sure. I know that by the time I attended Jarvis Christian College, which is a historically black college in Hawkins, Texas, that I had started making the connection in my head between objects, and political policies, and I guess what you would say would be social practices, and also I would have been probably 18 years or 19 years old at the time. I had started receiving invitations to address groups about the collection and so I had, what I used to call my bag of baddies, you have a bag of goodies, I had a bag of baddies. I tell you, there’s just something about an object that is different than a word. It’s almost self validating when you show a segregation sign, or a heavily caricatured object. It just changes the discussion. By the time I became a professor, at that point, I had many students who just thought Jim Crow was a period where it probably sucked to be black. You weren’t paid well, you were restricted to certain occupations as it were. There was probably some violence, but it’s not as bad as people are saying. So showing those objects gave kind of a legitimacy to my lectures, to my presentations. And then, I don’t think I’ve said this much, I suppose you would say I also became kind of an obsessive collector. I saw so many pieces in my life that I could not afford, and sometimes they were the worst pieces, but I became obsessed about what I could acquire. Each time I would look at an object, I would think, see if I had that, I could tell this story or that story. They were very functional for me. Now, the irony in the whole thing is that they were functional for the people that created and bought them, but in a different way.

MH: Right, yeah. The Jim Crow Museum uses the phrase, using objects of intolerance to teach tolerance. I think many people might think the word tolerance and intolerance are pretty mild in the context of this exhibit. Can you talk about why you choose the word tolerance, and what that means for you in this context?

DP: That, again, is a great question. You’re on a roll here. Years ago, I read UNESCO’s statement on dignity. It talked about tolerance. It seems strange today, but the way they define tolerance, it was the umbrella term. Underneath it came social justice, and some more ideas. I’m trying to think if we’ve been criticized more for something then our tagline. From the left, what we hear are people saying things like, “We don’t want to be tolerated.” This implies, in some way, that you’re trying to get to a point where we will be tolerated. From the right what I hear is, “Social justice is some left-wing, almost communist kind of a slogan.”

For us, the tagline, using objects of intolerance to teach tolerance and promote social justice seems to be a way of offending both the left and the right, but what I tell them both is this, It’s the work that matters. You know this sort of shape shifting of words and their meanings, I get that, I’m a sociologist, I know that. Even the words are only sound signs. We do give them meanings and that those meanings matter. I think what matters more for us is the actual work that we do. By the way, part of that work is people come into the facility, we debate the tagline but I also know that words change. People now are debating the word diversity. There's debate now the word inclusion. No one uses pluralism anymore. No one other than myself and one guy in California uses the word desegregation anymore.

There’s just this constant shape shifting of words, but the need for the work remains. So I’m committed to that, not going to just try to keep up with, when I say this is sounds harsh, and I’m not going to try to keep up with whatever it is that’s fashionable for us to call the work. I’m going to focus on doing the work.

MH: Mm-hmm (affirmative). How does one teach with racist, sexist, and homophobic objects?

DP: That’s, again, a good question. I had a colleague, she passed away years ago, I miss her to this day, Tamzie, she was an artist. She and I used to have some classic knockdown drag out debates. One of them dealt with which we should call the traveling exhibit that’s actually in this facility. She kind of liked the idea of calling it Nasty Art. I got that, but I didn’t like the word art being used, because to me, art was this, the whole beautiful, aesthetic, challenging aesthetic kind of thing. Not racist and sexist postcards and the like. Somewhere in the process of our arguing, she introduced me to visual thinking strategies. It’s been a struggle for me, but part of it is, when people come into our facility, we ask them, what is it they see?

I’ll tell you a story that’s not in the book, it happened shortly thereafter. I was at Western Michigan University giving a talk. One of my colleagues, actually, an old student, Kalid Al Hakeem showed up, and he, himself, has created the Black History 101 Mobile Museum, in part because I challenged him to do something - to do that. And he brought a few objects with him. I think one was a mammy, and quite frankly, I’d don’t remember what the other thing was. They were both caricatured kinds of pieces. Here we are, after my presentation I gave a workshop. The students were art students. I don’t know what race people are by looking at them, but if I had to guess, I would say most of them presented as white Americans. He and I don’t. We sat around, and there were probably 13 or 14 students or so. What we did was we passed around, I think one was a doll, baby doll.

We passed it around, and I used a kind of visual thinking thing, which was, tell me what is it you see when you look at this. We have very few ground rules, no hitting people, no yelling at people, none of that stuff. Just listen, don’t interrupt, and just say what you see. You don’t need to comment on what someone else sees. Oh my goodness, I wish I had videotaped that. It was the most profound thing. It amazes me still how two people, or three people, or 13 people can look at something so differently. One person looking at it, a character doll, they see themselves sitting on their grandfather’s lap many years before. They’re not being flippant, they’re not being disrespectful, it’s in a true sense nostalgic. Someone else sees that same doll as a kind of remnant of slavery and segregation, and they’re looking at the same doll.

Once again, for a myriad of time, it reminded me that that’s how we look at race, and maybe that’s how we look at many, many other parts, other related topics in terms of social justice is that we’re not seeing the same thing. Not only are we not seeing it, which is okay, we’re not listening to what the other person sees. That’s the value of a conversation like that, and it’s the value of the museum itself. Because people come in, and they get an opportunity to listen to what other people see. Now, they also get, because we were at a university, they also get a solid and accurate, and I hope objective treatment in terms of the didactic panels that they read. I’m shocked sometimes how little people know about Jim Crow, about the era. That’s what college is, isn’t it? It’s a place to go and learn.

MH: Yeah, well, you touched on the next two questions actually.

DP: So that means we can skip those?

MH: You said at first that I wanted to ask you if you considered these items art. If so, at what point do they become art?

DP: I don’t, at least in the main I don’t. We actually have in the museum, four pieces. One that I created where African-American artists try to deconstruct, through their art, some of the caricatures and stereotypes. That I do believe is art. I certainly believe that there is an artistic quality to a lot of the flat pieces. Yeah, there’s that part of me, and by the way, I’m speaking it as if I’m some kind of art expert. I know next to nothing about art, okay? But I don’t know, and this is what I used to tell Tanzie all the time, and I’ll take an extreme case, because that’s how people make their points in this culture. You show me a picture of an African-American male being beaten on a postcard, we have many versions of that, it’s an image, it’s a provocative image, it’s an image that can be enlarged, matted, framed, and it can look like just any other piece of art. That wasn’t what it was. It was a postcard. You can certainly argue that pieces that represent propaganda can also be art and it was propaganda, but just seems like calling it art dignifies it, it doesn’t just legitimize it, but that it dignifies it in some way. I think that’s the part that I struggle with, but I could see people seeing it differently.

MH: Right. So, this is one of those help the white people questions, just preface it like that.

DP: Okay, the answer is see, get out.

MH: It might be harder for some people to understand why some items in the exhibit are anti-black, photos of people being lynched, or clearly anti-black and violent. But particularly in the South, I wonder if people ask you, “What’s wrong with Aunt Jemima?”

DP: Oh, I love the question, “What’s wrong with?” It gives me an opportunity to say something that we don’t say enough until you get to the actual facility, which is, despite the name of the facility, which I would change tomorrow if I could, a piece does not have to be racist to be in there, it just has to be useful to help me teach about race, race relations, and racism. I also get related questions, which someone will say to me … now, keep in mind, this is a person who just walked past a lynching tree in there, and they walked past some other really heinous, direct affronts to human dignity. Then they’ll get to a kitchen where we'll have Aunt Jemima, Aunt Sally’s syrup, or Aunt Donna’s syrup, or something and they’ll go, “Aha, what’s wrong with this? How is this racist?” Again, my response to them is I’m not saying it’s racist, but what I want you to tell me is what is it you see? Do you see a connection between everyday objects which show blacks as servants, as menials, often in physically caricatured ways. Can you see a relationship between those millions of depictions, and the subjugation of black people economically, and politically, socially, and whatever? Because that’s our focus really, it’s on the everyday object. It’s on, what you might refer to as, the borderline object. I think we have much better discussions when it’s about a caricatured mammy pillow, then it is about the word, nigger, or a lynching postcard, or something. Because I think most people just sort of summarily dismiss those pieces as being racist, and move on. Whereas real discussions occur when we can disagree about where the boundaries are.

MH: You know for myself, I spent many years of my particularly younger life calling out examples of misogyny. I didn’t collect artifacts, but I studied them. I consumed media. I wanted to understand the industry that supported violence against women. One day I just couldn’t do it anymore, I couldn’t look, I couldn’t read it, I couldn’t watch it. It was like some kind of switch turned off in my brain. I wonder, have you ever experienced anything like that with this work that you’ve done?

DP: Okay, so now you’re in my brain, and I’ll give you what I mean by that. Recently, I was watching a Motown commercial celebrating, I don’t know, 25 years, a million years, however long it was … It was one of those infomercials. It was one that had Michael Jackson doing the moonwalk. I’m watching this commercial, and it’s got to be three, 4 o’clock in the morning, because I’m up reading and doing research. I just had this thought. I looked in the audience, and there were these well-dressed people, most of them were, at least the ones that were shown, were African-Americans. Again, you can’t judge peoples class standing by their clothes, but they looked well-off. Obviously, the people on the stage were celebrities, and presumably wealthy, and I had this thought, and it stayed in my head for a few seconds, and it was this, why am I doing this stuff? Why don’t I just dance? It was a kind of a eat, drink, and be merry kind of thing. Just ignore this. What the hell is my problem that I’m spending my life -I’m not exaggerating, I’m not making this up, I had this thought in my head. Then it passed. Now, it wouldn’t have stayed a long time anyway, because I know that whether I document, and we don’t just collect objects from the past, I mean President Obama was a cottage industry for racist objects, just like Hillary Clinton was a cottage industry for sexist objects. So whether I dance or not, whether I close my eyes to what’s going on, it’s still happening.

If you have a race-based incident nationally, there is going to be a two-dimensional or three-dimensional object created within the week. I know it because we’re still buying those objects. Whether I dance or not, it’s still going to happen. Also, I would bet you that almost, if not all, of the images that are in the Jim Crow Museum, are still being created. We have a section that’s called New Objects. That is not to suggest that we are not more egalitarian as a nation than we were in the 1930s, or 40s, or 50s. It is to suggest that the sort of battle and struggle over racial imagery still exists in our culture. I would suggest that I feel, well, I saw us, and this was naïve in my brain, and I should know better, and I should have known better, I saw us progressing. I saw the progress as linear, like you weren’t going to take a step back. In the last couple years, I’ve had to, not just reassess that, but I don’t have the same hope that I did. I’m not crushed or anything, but I don’t have the same hope that I did that the line is as straight, and that the progress is as inevitable as I thought. We were having such a positive conversation, and then you asked me this question, it brings me down.

MH: Well, I can relate to that. I feel like, in a lot of ways, when you see my background undergraduate is in women’s studies, and when you see, there are many times and me, oh, here’s this one step forward, and now we slide back. This backlash every time there is a little bit of progress, there’s a backlash that goes with it. I do feel like, and maybe this is just the Pollyanna in me, that even though there is backlash, the awareness that went with that progress is still there. It didn’t go anywhere. It makes the backlash that much harder.

DP: I hope you’re right. I started collecting sexist objects about a decade ago. We have, probably now, a couple thousand. Those objects are in the room which used to house the Jim Crow collection. We’re starting this new journey now to try to build this Ferris Museum of sexist objects. It won’t be a Women’s History Museum, just like the Jim Crow Museum is not a Black History Museum, or African-American History Museum, they are what they are. They’re the objects that the other museums keep in their basements. I just think, as a culture, you have to deal with the ugliness sometimes. There is a metaphor Dr. King used where he talked about, if you want to get rid of racism, really get rid of it, you have to view it as a boil. I don’t know the scientific name for a boil, but I think of them as disgusting.

MH: Boil’s a good name for something disgusting. I think that definitely conjures up a good image.

DP: Yeah, and so he said that you have to lance it and let all the venomous, disgusting puss come out. That’s how I see this, and that’s how I see the work that we do. Not to be defensive or anything, but sometimes when we receive criticism about our approach being too direct, again, this does sound defensive, but what I say to people is is, okay, I can accept that our approach dealing with racism, or sexism, or homophobia, or any of the other injustices may be too direct for some people. It’s the way that’s working for the work that we’re doing, but I need you to go do something. It’s easy to stand on the bank with your pant legs dry, and complain about the way people are cleaning rivers, but get your ass off the bank and go out and do something.

Actually when we opened, and this is weird, when we opened in 2012 there was a London survey, it was done by The Telegraph, the newspaper in London, and they asked their readership whether or not we should open. I thought, okay, so first of all, that’s really cool that they are talking about us in London. Secondly, I am a little interested in what the people said. It was almost like 80% said we should, but third, I’m not reliant on them whether or not we’re going to open or not. What it did remind me of too was the biggest supporters of the work we do are the people who see the work we do.

For the ones who don’t see it, we’re kind of an abstraction. Then they have to fill in the blanks and imagine. They imagine us as a shrine to racism, or a shrine to sexism, depending on which facility. We’re neither of those things. I can’t tell you the number of people who come, and they’re surprised that it’s high-quality, that it’s not polemic, it’s not ideological in the way they thought. It’s very much historical. One of the reasons for that is, you don’t have to be extremely polemical, or you don’t have to be at all, because if you just tell the story, the story itself is a story of injustice. Unless you’re lying, it’ll tell itself. Then the objects, and this is something Tamzie used to say all the time, that she had a hard time talking in the facility, in the museum, because the pieces were talking. She couldn’t hear me, because she’s surrounded by these thousands of pieces screaming at her.

MH: Sure, yeah. In your book, Understanding Jim Crow, you described this time when your children were playing with one of your anti-black racist artifacts, and you collected it. At one point they broke it. You were angry with them. I think, in this case, it was an accident when they broke it, but I wonder, when you mentioned this in your book, it was almost in a side in your book actually, but I wonder if you recall that time that you smashed that artifact you first purchased, and just thought about the difference between the experience and the one that your children had had.

DP: Yeah, I think about it every time we drop something in the storage area. Yes, for that particular case, yeah, the irony is not lost on me that here I am screaming at them for accidentally dropping something, and there I was trying to make what, in my, 12, 13, 14-year-old mind it was some kind of statement. I am pleased these days, and at the time I had two daughters. I don’t know if my son was around at the time, but their lives are, they think of themselves as social justice warriors. They enjoy telling the story. Except, at some point, I think they were going to start saying they did it on purpose. The practical part of that was it was sort of a bell ringing telling me, get that stuff out of my house.

Quite frankly, I tried to first give it to Howard University, but we just couldn’t come up with an understanding of, are you going to show this? Are you going to preserve this? Or whatever. Then I realized I had become, in some ways, either attached to the collection, or I just didn’t trust other people. I didn’t trust to not be around when people made decisions about it. I ended up donating it to Ferris, which made all the sense in the world. If you know our founder, Woodbridge Ferris, who listened to Frederick Douglass as a child, who brought Booker T. Washington to our school, who preached Booker T. Washington as eulogy, who set up a program bringing black kids from Hampton to Ferris, kids who changed America, I’m serious. Belford Lawson, the first African American to win a case before the United States Supreme Court was one of them.

Percival Prattis, the first African-American journalist admitted to Congress in that gallery. There is so many of them, and they did such wonderful things. Our founder created that, and he had no tolerance for racism. Zero. He brought in international students. He had no tolerance for sexism. This guy was so far ahead of his time. That’s what I tell people all the time, he’s in my top 10 people. Period. That’s not some crap from advancement in marketing. That’s me really meaning that. These folks will say “Well, why is this museum at Ferris State University in Big Rapids, Michigan? Because it was possible there.

MH: Sounds like it’s where it needs to be.

DP: Well, and with the Internet, we have a pretty good virtual presence. That can go all over the world. It wouldn’t matter where you work, where your home-base was.

MH: Looking back, particularly the first four years of the Obama Administration, there was this hopeful talk about a post-racial America, and even President Obama helped perpetuate that, I think, a little bit. In the second half of his presence, it became clear, even to those Pollyanna of us, and I think I was one of those, there was not a post-racial America. Then we moved into this election season, and postelection time period, during which conversation has become increasingly blunt. That’s probably not blunt enough saying that.

This is where, I kept thinking about this this morning, trying to figure out how to phrase this question, but I guess I find myself wondering if this new, in-your-face approach to communicating about matters of race and discrimination, is more useful to dealing with issues that have been largely unspoken for a couple of decades. Which is almost the opposite of what you were saying a few minutes ago about finding those borderline objects to talk about. I don’t know. It’s like we didn’t want to talk about, we’re just so worried to dance around things, and no one wanted to discuss stuff that was clearly a problem. Now, it’s just so honest, ugly, and in our faces in some ways that we can’t put our heads in the sand.

DP: Well, I agree with you that things have changed. On a personal level, and also professional as it relates to the museum, they haven’t changed that much for me. Because we were having those kinds of really difficult, painful, ugly discussions for the last 15 years in the facility. When I traveled the country, because of my work, people assumed that we should continue those, and that was good. I’ve been hearing the ugliness for a long time, but there is no doubt that there is a kind of racist rant, which is, I don’t want to say it’s yet mainstreamed, or its reemerges as mainstream, but it is reemerging in the mainstream more often. There are more people willing to say things that are not racist, but that are racially insensitive. Then there’s just people just asking questions that they had, depending on who’s listening, that may sound racist or racial. So the opportunities, and I have to try to look at these as opportunities, otherwise I can’t be an educator, I just have to. I think the opportunities will be greater in frequency, and in intensity, and duration. We've started to see that. What do I mean by that? I mean I am going to have, you’re going to have the nations going to have many more opportunities to have sustained dialogue, and by that I mean 9, 10, 12 times the people sitting and talking. Quite frankly, we should have been doing that all along. You shouldn’t have to go to a Jim Crow museum to have difficult conversations about race, or you shouldn’t have to have a black guy lying, is it laying or lying, in a alley, dead, to have difficult conversations. Or a famous black ex-football player being charged, and then found not guilty, or not convicted rather, in order to have conversations. We just need, as a nation, to recognize that race, and race relations, and sex, and sexism, and these areas, they’re just not areas where you ever finish, and that’s okay to not finish. If you’re going to be a mature nation, you have to understand that we have to be vigilant about relationships, including dealing with really hard parts, of not just history, but the present. On the one hand, I am almost discouraged at the racist, and sexist, and homophobic, and ablest rhetoric that I heard during the most recent presidential election.

Quite frankly, discouraged to see people that I know aligned themselves with white supremacists, thinking in positions of power in our nation. Yeah, that’s extremely discouraging. On the other hand, I do recognize the value of people having direct conversation. I’m not afraid of a conversation. I believe in the triumph of dialog. How else can you be enheartened if you don’t believe in that? So I was a little down there for a while. We’re having more and more people visit the facility. Not necessarily saying that I am enthused about some of the conversations we have to have, but it’s the work we do.

MH: At the Jim Crow Museum at Ferris State, you have a space dedicated to reflection. The room where people can ask themselves, “What can I do today to address racism?” As a institution of higher education that’s trying to answer this question from an institutional standpoint, Appalachian's one of those places that brought you here for consultation and advising. What advice are you sharing with administrators, faculty, staff, and students about what we can do today to address barriers to making our campus a more inclusive place?

DP: Well, that’s great. Well, first of all, I’ve had a wonderful time here. I’ve enjoyed the conversations that I’ve had. People are unusually nice here. I don’t know if they’re up to something. I’m just joking. Everybody’s been very kind. We’ve had some good conversations. I think, as might be expected in some of the groups, there is been some reluctance to really just jump right in. Folks don’t want to say the wrong thing, don’t want to be perceived in a way that they don’t perceive themselves.

How do you get past that? Well, you just got to keep talking. Eventually, you get to a point where it’s almost like assessment in higher ed where, when it first came out it was like, oh my goodness, this is just more work. I don’t even know what this is. I don’t know the value of it - whatever. I kind of think about difficult dialoguing around issues of justice like that. At first, it’s just people are wondering, why do we have to do this? Or this is hard. Or they’re looking at possibly bad scenarios that could come out of that. But if they keep talking. What I’ve seen, again, I sound like I’m, I used the term Polly Annie. What was the term?

MH: Pollyanna.

DP: Pollyanna, yes. Yeah, I usually just say naïve. I know it sounds like that, but I’ve seen so many people come into our facility, and come back. Because you don’t change people. It’s not like Saul on the road to Damascus, and you get struck by lightning and become the apostle Paul, it’s work. It means coming back and having more and more conversations, and eventually taking some chances. And then not being punished for taking the chances. It’s creating a culture where we’re just okay. It’s okay to be wrong. It’s okay to be different. It’s okay to engage people. You don’t have to win the conversation. You don't have to win. I like a lot of what’s happening here. I have to tell you. Just again, listening to the conversations, listening to talk about some of the programming that you have in place. You’re doing a lot of things right here.

The thing that I would do right now is, and again, I’m coming here telling you what to do, but I would focus on engaging my entire campus to be involved in conceptualizing an inclusion, diversity and inclusion plan. It took us seven months, as a campus, to decide what’s diversity for us. It took another few months for us, as a campus, to decide what’s inclusion for us. We’ve had people say, well, you know, can we use your definition of diversity, inclusion? It’s like, well, I’d rather you didn’t. In part because it’s ours. It may not even fit who you are.

Trying to find a way to engage, and I mean really engage in a way that’s kind of scary quite frankly, but to engage the whole campus in deciding who you are, where you want to go, how you want to get there. And how do you get there? By creating a campus where everybody believes it belongs to them, as much as it belongs to anyone else. That’s probably the best definition of what justice is, what inclusion is. We, as a nation, haven’t gotten there, and most of the institutions haven’t gotten there.

MH: Wow, you make me ready to roll my pants up and jump in the water for sure. Thank you so much, Dr. David Pilgrim, it was my pleasure and absolute privilege to speak with you today.

DP: Thank you. You’ve been very kind.

MH: Today’s show was written and produced by Troy Tuttle, Dave Blanks and me, Megan Hayes. Our sound engineer is Dave Blanks with assistance from Wes Craig. Our web team is Pete Montaldi, Alex Waterworth and Derek Wycoff. Research assistance comes from Elisabeth Wall and video and photo support come from Garrett Ford and Marie Freeman. Our theme song was written and performed by Derek Wycoff of Naked Gods. Our podcast studio is dedicated to Greg Cuddy and a special thanks to Stephen Dubner for inspiration, advice and moral support. SoundAffect is a production of the University Communications team at Appalachian State University in Boone, NC. Thanks for listening. For SoundAffect, I’m Megan Hayes.

What do you think?

Share your feedback on this story.

Listen to podcasts recorded during the weeklong series of events held in March, 2017

Conversations with smart people about stuff that affects our world, and how we affect it

About Appalachian State University

As a premier public institution, Appalachian State University prepares students to lead purposeful lives. App State is one of 17 campuses in the University of North Carolina System, with a national reputation for innovative teaching and opening access to a high-quality, cost-effective education. The university enrolls more than 21,000 students, has a low student-to-faculty ratio and offers more than 150 undergraduate and 80 graduate majors at its Boone and Hickory campuses and through App State Online. Learn more at https://www.appstate.edu.

![The Search for Vertical Grasslands [alumni featured]](/_images/_posts/2026/03/vertical-grasslands-600x400.jpg)

![How NCInnovation Is Rethinking Economic Development in North Carolina [faculty featured]](/_images/_posts/2026/02/rethinking-economic-development-600x400.jpg)