Dr. Sarah Carmichael, professor in the Department of Geological and Environmental Sciences at Appalachian State University, is a geochemist and a National Geographic Explorer. She specializes in Devonian period research, studying the causes and effects of mass extinction events that occurred 350–417 million years ago. She is pictured during a field expedition in Mongolia in 2018, where she and her team evaluated specimens preserved in volcanic rocks. Photo by Felix Kunze

BOONE, N.C. — Appalachian State University’s Dr. Sarah Carmichael describes her job as similar to that of a crime scene investigator — and the evidence she examines is more than 350 million years old.

Carmichael — a geochemist, a National Geographic Explorer and a professor in App State’s Department of Geological and Environmental Sciences (GES) — specializes in Devonian period research, studying the causes and effects of mass extinction events that occurred 350–417 million years ago.

“The Devonian period contains pulses of extinctions that, taken together, constitute one of the top five most severe mass extinction events in Earth’s history,” Carmichael said. “The events decimated coral reefs and marine ecosystems and changed the evolutionary trajectory of fish.”

Many scientists have studied these extinctions — thought to be caused by anoxia (oxygen loss) — but the reasons behind the change in oxygen levels remain a mystery, Carmichael said. For clues, scientists study fossils and chemical compositions preserved in rocks.

“It’s like we’re doing a crime scene investigation. We’re sifting through trace evidence, trying to figure out who was there and what they might tell us if they could talk. Has there been ‘tampering with the evidence,’ through the interaction of rocks with groundwater, that might alter the chemical signals? We want to know what was going on before, during and after the extinction,” she explained.

In 2018, Appalachian State University geology professor Dr. Sarah Carmichael, App State students and other members of the DAGGER (Devonian Anoxia, Geochemistry, Geochronology and Extinction Research) team traveled to Mongolia to study late Devonian extinction events. Carmichael is pictured third from right, at the field site with her colleagues from Mongolia. Also pictured, third from left, is Olivia Paschall ’19, who has since earned her B.S. in geology from App State and is now pursuing her doctorate at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. Paschall said Carmichael was “a powerful role model and wonderful mentor” to her. Photo by Felix Kunze

By studying extinction events from the past, Carmichael said scientists can look for similar trends in sediments today — and better understand and predict potential outcomes.

Carmichael is one of the lead scientists on an international, interdisciplinary team known as DAGGER (Devonian Anoxia, Geochemistry, Geochronology and Extinction Research), along with the following GES department faculty and staff:

- Dr. Cole Edwards, sedimentologist and assistant professor.

- Marta Toran, outreach coordinator.

- Dr. Johnny Waters, professor emeritus.

They collaborate with a number of paleontologists, geologists, stratigraphers, geochemists and other scientists from around the world, coordinating expeditions and passing along rock samples from scientist to scientist to be analyzed within each one’s specialty.

DAGGER was formed in 2015, coordinated by faculty at App State. Its work has been funded by a variety of sources, including the National Geographic Society and The Explorers Club, and the team was recently awarded a grant of $459,988 from the National Science Foundation (NSF) to continue its research.

Dr. Sarah Carmichael, a professor in the Department of Geological and Environmental Sciences at Appalachian State University, traveled to Mongolia in 2014 and 2018 with members of the DAGGER (Devonian Anoxia, Geochemistry, Geochronology and Extinction Research) team to study mass extinctions from the Devonian period. While many scientists have studied these events, most of their samples were from the U.S. and Europe, and current knowledge is limited by this sampling bias, Carmichael said. To address this bias, DAGGER members focus their research in understudied paleoenvironments in southwestern Mongolia, Germany, Belgium, northwestern China and Vietnam — so they can compare samples across a wider range of geography than has been attempted before. Carmichael took this photo of the field site in Mongolia in 2014. Photo by Dr. Sarah Carmichael

Student investigators

Several undergraduate students at App State serve on the DAGGER team each year. In the past, students have traveled to Mongolia, Belgium, the western U.S. and elsewhere to gather and study specimens in the field, further analyzing samples and data back in the lab on campus. While travel has been paused during the COVID-19 pandemic, lab work has continued.

“The project has provided long-term mentorship and laboratory training of numerous undergraduate researchers,” Carmichael said.

Now, in addition to supporting DAGGER’s continuing research, the recent NSF grant will provide an opportunity to share the science with younger students, in grades 6–12.

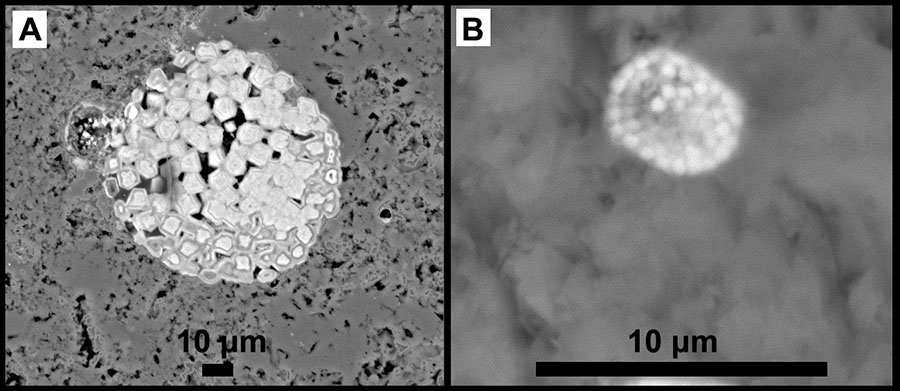

In the College of Arts and Sciences microscopy facility at App State, Dr. Sarah Carmichael and her team use a scanning electron microscope to examine chemical signals preserved in fossils — to study causes and outcomes of mass extinctions during the Devonian period. The two slides pictured show pyrite framboids (a micromorphological feature with an appearance similar to raspberries). The large framboid on the left formed in water with sufficient oxygen. The close-up image on the right shows a much smaller framboid that was formed in oxygen-deficient water. Photo submitted

Over the next three years, Carmichael, Edwards, Toran and their team of student researchers will produce videos and interactive materials for an online learning module called CSI: Devonian — a name Carmichael and Waters have used informally to describe their research for several years.

The course components, aligned with Next Generation Science Standards, will include videos of research expeditions in the field as well as laboratory work at App State.

Through the learning module, Carmichael said middle and high school students will learn about the mass extinctions in ancient history — using the videos in combination with data sets provided by the DAGGER team to develop their own scientific conclusions about what may have happened.

More importantly, Carmichael said they will learn about how scientists collaborate on real-life projects, using evidence to form scientific explanations.

“Students sometimes imagine scientists working alone in a lab, which can be intimidating. We want to show how scientists work together to find solutions and have fun in the process,” she said.

What do you think?

Share your feedback on this story.

As an undergraduate at Appalachian State University, Cameron Batchelor ’15 was part of the DAGGER team that traveled to Mongolia to study Late Devonian extinction events. Pictured, from left to right, are Dr. Johnny Waters, professor emeritus in App State’s Department of Geological and Environmental Sciences (GES), Batchelor and Dr. Sarah Carmichael, professor in the GES department. Photo submitted

Geochemist joins John Glenn, Sally Ride, Sir Edmund Hillary, Jane Goodall and other well-known explorers in this prestigious society

About the Department of Geological and Environmental Sciences

Located in Western North Carolina, Appalachian State University provides the perfect setting to study geological and environmental sciences. The Department of Geological and Environmental Sciences provides students with a solid foundation on which to prepare for graduate school or build successful careers as scientists, consultants and secondary education teachers. The department offers six degree options in geology and two degree options in environmental science. Learn more at https://earth.appstate.edu.

About the College of Arts and Sciences

The College of Arts and Sciences (CAS) at Appalachian State University is home to 17 academic departments, two centers and one residential college. These units span the humanities and the social, mathematical and natural sciences. CAS aims to develop a distinctive identity built upon our university's strengths, traditions and locations. The college’s values lie not only in service to the university and local community, but through inspiring, training, educating and sustaining the development of its students as global citizens. More than 6,800 student majors are enrolled in the college. As the college is also largely responsible for implementing App State’s general education curriculum, it is heavily involved in the education of all students at the university, including those pursuing majors in other colleges. Learn more at https://cas.appstate.edu.

About Appalachian State University

As a premier public institution, Appalachian State University prepares students to lead purposeful lives. App State is one of 17 campuses in the University of North Carolina System, with a national reputation for innovative teaching and opening access to a high-quality, cost-effective education. The university enrolls more than 21,000 students, has a low student-to-faculty ratio and offers more than 150 undergraduate and 80 graduate majors at its Boone and Hickory campuses and through App State Online. Learn more at https://www.appstate.edu.