Appalachian biology professor Dr. Shea Tuberty and former FEMA Administrator Brock Long discuss how developing a culture of preparedness fosters resiliency

What happens when the FEMA Administrator and a water quality expert and biology professor start talking about resiliency and the effects of climate change? The discussion moves from what it's like being on the front lines of America's worst disasters, to the interplay of environmental, social and economic resiliency, to how Appalachian is cultivating resilient students.

Transcript

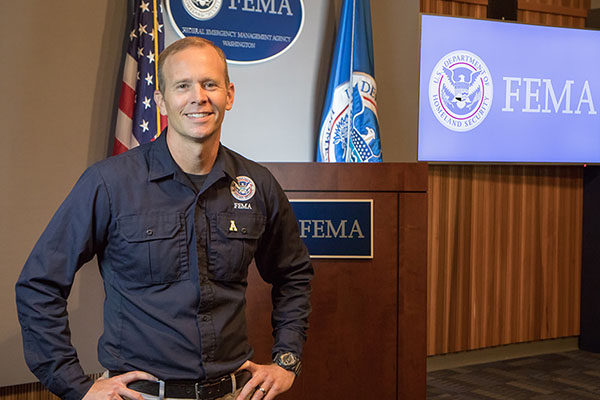

Megan Hayes: Today I'm joined by Brock Long, Appalachian alumnus and administrator of the Federal Emergency Management Agency, who's joining us via telephone from FEMA headquarters in Washington, D.C., and Dr. Shea Tuberty, professor and assistant chair of Appalachian Department of Biology, who's here in the Greg Cuddy Studio to talk about resiliency, and specifically, what it is and why it is important to plan for our environmental and social systems to have the capacity to absorb disturbance or disaster and still retain basic structure and functionality. So, Brock Long and Shea Tuberty, welcome to SoundAffect, and thank you for taking the time to join this conversation today.

Megan Hayes: So, I'd like to start with asking each of you the same question. And, Brock, if you wouldn't mind responding first, since you can't see each other to make eye contact. But my question is, what is resiliency?

Brock Long: Well, from where I sit as FEMA administrator, it's a community's ability to bounce back from disasters. It's that simple. But we've got a long way to go in this country to creating a true culture of preparedness and creating resilient communities.

Megan Hayes: And Shea, let me ask you the same question.

Shea Tuberty: So yeah, resiliency, I use that term almost interchangeably with sustainability, but resiliency, to me, means kind of elasticity. So, being able to flow with the punches or go with the punches, as Brock mentioned, just building infrastructure to withstand a catastrophe and then respond quickly afterwards with continued capability.

Megan Hayes: And Brock, can you talk about why resiliency is so important on a national scale?

Brock Long: Unfortunately, we're in a vicious cycle of communities being impacted by disasters and having to constantly rebuild. And it's almost as if we're not learning anything from what history, mother nature and history has taught us. Specifically, if you look at the last 16 months since I've been in office, FEMA has rendered more individual assistance, money into the hands of those who are uninsured to devastating losses or public assistance, money that goes into fixing infrastructure. We've rendered more individual and public assistance in the last 16 months than the agency has done in the previous 38 years combined. That's our entire history basically packed into a year and a half.

Megan Hayes: Wow.

Brock Long: We got to stop the cycle. And so it's going to take different approaches, and that's what we've been working on every day up here in FEMA since I've been in office.

Megan Hayes: Shea, can you talk about the resiliency work that you're doing regionally?

Shea Tuberty: So here at the university, there's a number of efforts to try to build our resiliency. Most of those have been around trying to deal with the flooding events here in Boone. So, along with what Brock just mentioned, this is a banner year for the High Country as far as flooding events. I've measured six high flow events this year so far, which is a new record in the last 40 years. I suspect by the end of the week we'll have our seventh, when these two feet of snow begin to melt and we get another inch of rain or so. Really, it's about flooding events, the impacts on town and county operations, folks that are living in the flood plain, and even university operations are impacted significantly when we've got, you know, Rankin West in the flood plain and having routine mud cleanups on the first floor from flood waters entering the building. So, this is something the chancellor's got her eye on and we're trying to put more effort into it. Our emergency management office on campus is starting to plan for the future. I think it's going to have an impact on our building and maybe raising buildings around the flood plain.

Brock Long: Shea, back in the Clinton administration, Boone was actually designated a FEMA project impact community, one of eight pilot communities, for that very problem that you speak of. So, flooding in that area is obviously not a new issue in Boone, but because we're trying to pack so many people into such a crowded area, the built environment is adding to those issues. But I guess the real question is, when we made that designation well over a decade ago, what changes have actually occurred or been sustained to further reduce flooding — not taking actions or building in a manner that increases it?

Shea Tuberty: Correct. So, you know, I think so far there's been three or four million dollars spent on restoration projects in different places on campus and downstream. And really, there's a number of us in the natural sciences that look at these as Band-Aids. They're really not preventing the problems; they're trying to make it look nicer. And so, it's really more of a public perception effort than it is correcting the issues. Ands so, I think on, on the horizon, we're talking about daylighting the creek on campus and decreasing the footprint of Peacock Parking Lot, which is enormous right now. And I think we could park more cars in a smaller footprint, open up more grassland, and create some wetlands around that that would be aesthetically pleasing and also functional. So, those kinds of things need to be in our future.

Megan Hayes: Brock, I'm not sure most people really understand FEMA's role in an emergency or disaster situation. I think we see FEMA on television, but I was wondering if you could tell us what FEMA does exactly? What can Americans expect from FEMA during an emergency after they face a major catastrophe and also, to your point, before those emergencies happen?

Brock Long: So, interesting enough, when I came into office, our mission was not very clear to the public. I mean, it's a long, drawn-out definition that we shortened and we made it very simple. You know, our job at FEMA is to help people before, during and after disasters, and our vision is to create a prepared and resilient nation. Now, to do that, we have several divisions that work to accomplish many different things. For example, as FEMA administrator, I'm also responsible for making sure that the entire executive branch of government remains in a capacity to be able to meet its mission and essential functions regardless of any threat realized to the nation, which is a huge job — continuity of operations to the entire executive government. I'm also one of the largest insurers in the country. I run the National Flood Insurance Program, but basically coming into this job, I've learned that the National Flood Insurance Program is not financially solvent and the business framework needs to, needs to change. There's a big myth on the need for flood insurance, and people think that if they're not shown in a flood insurance special flood hazard area that they don't need flood insurance for their home, and that's not true. Any home can flood. So, you know, not only do we run that program, we also run a preparedness program that puts out two billion dollars’ worth of preparedness grants to prevent anything from acts of terrorism to natural disasters. And then we also have a very robust response and recovery division, which has been way too busy right now, you know, helping people save lives and put communities back together. What we're really also trying to focus, under our new strategic plan, we’ve developed a whole community plan that has three very simple but ambitious goals that we're trying to get not only FEMA to move into this direction to accomplish, but all of the government down through the different layers at the state and local level, as well as the private sector to help us accomplish these goals. So, goal one is develop a true culture of preparedness. Goal two is to ready the nation for catastrophic disasters with a focus on low to no notice events like large earthquakes or wildfires like what we just saw in Paradise. And then the third goal is reduce the complexity and cut out all the bureaucracy when it comes to how we can render assistance. And specifically, we have a goal of, you know, how do we rebuild these communities to a higher standard than the way they existed before the disaster? And Congress has given us the authority to be able to do that through the Sandy Recovery Improvement Act.

Megan Hayes: Can you talk a little bit about what that looks like? How the planning FEMA does for natural disasters and other emergencies, including building the budget for Congress to act on?

Brock Long: Yep. So, in the past, before the Sandy Recovery Improvement Act, we basically had only the legislative authority to rebuild a community to its pre-disaster condition. OK? Which is a very regressive approach, and it wasn't doing us any favors. And with the passage of the SRI Act after Sandy, it implemented what's called Section 428 of the Stafford Act, which is the guiding document of what we can and can't do as FEMA. Well basically, this is a term for outcome-driven recovery to where now, when we rebuild infrastructure that's blown out from a flood, or a fire, or a hurricane or whatever, it allows us to do so in a mitigated and resilient fashion so that we're not rebuilding this thing again in the future. The other thing that happened, that we're trying to wrap our head around, was transformational legislation. I testified no less than 14 times in Congress since being in office and was begging Congress to do more about pre-disaster mitigation funding being available before disasters hit, on blue sky days. So with the Disaster Recovery Reform Act that just passed several months ago, six percent of all recovery dollars spent by FEMA in any given year will now be put upfront in pre-disaster mitigation. So if that bill had gone into place last year, there would be roughly $2.5 billion this year in pre-disaster mitigation funding up for grabs for state and local governments to do large-scale mitigation projects. So, for the first time in history, you know, we really have put a massive bulk of pre-disaster mitigation on the front end to start making a dent on the back end, you know, ultimately to save lives and reduce the impact of disasters on infrastructure and property.

Megan Hayes: Wow. So Shea, on the local level — you referenced this just a minute ago — we just experienced a record-setting snowfall event here in the High Country. We're still digging out, some of us are, from that. Talk a little bit about what kind of impact this weather event has on our ecosystems here in the High Country, at the top of the mountain, and also other ecosystems that are impacted by what happens here.

Shea Tuberty: Well, there's a number of ecological impacts. Certainly the depth of the snow and the weight of it impacts the vegetation here. And I think everybody's witnessed the broken limbs, loss of power. Although, you know, amazingly, very few people lost power up here, even though, off the mountain, we were hearing hundreds of thousands. So, that says something about Boone and the county as far as being prepared. And it also means that we've had so many damages in the past that we've had to rebuild in a way, like Brock was saying, in a way that's not going to just keep getting damaged. So, that was good, but the other impacts have to do with how humans respond to the snow. And typically, that's been met with laying down lots of salt on the streets. So, everyone in Boone that's been here any time over the winter knows that our roads tend to be salt-encrusted at certain times, preparing for an oncoming snow or ice storm. This was no different, and the good news is that they didn't lay down, you know, an extra foot of salt, thinking that we're going to get an extra foot of snow. And so, the amount of salt that was put down was probably on par with what they usually put down. But as the snow melts, and that salt is dissolved, it's moved right into the creeks. And that's kind of my role on campus with sustainability and water issues right now, is measuring not just the creek that runs through town, Kraut Creek or Boone Creek, but also, you know, another seven or eight that contribute to the South Fork of the New River. You know, there's a lot of data that shows that the money you spend on putting rock salt on roads is repaid within 30 minutes just in saved lives, damaged cars and other personal land holdings. And so it's hard to make the argument that you shouldn't be using salt. Asking people to be patient and let the snow melt and ice melt isn't going to happen. And then there's numbers that, you know, are in the tens of millions for bigger cities if you shut them down because of road impassability, you're losing huge amounts of income. So, asking people to do that isn't going to happen. So, adding the salt seems like it's going to be something that's going to be around a while, but what I've been looking at is the impact on the water quality. And, you know, basically, there are moments in Boone that the water is as salty as it is in the estuary environments where rivers are meeting the oceans at the coast. And so, the animals here and the plants here that live in our streams are certainly not adapted to that kind of salinity. So we've been looking at the long-term impacts, short-term impacts, the pulsing impacts of salt impacts to our streams.

Brock Long: Shea, you know, it's funny. You just triggered something that’s a big problem for FEMA is you were saying the lack of patience is driving some of the decisions with how we attack things. Well, the lack of patience is the biggest enemy of FEMA when it comes to the disaster recovery. So, often we're under such pressure to be able to restore critical infrastructure in an unmitigated fashion because people want their toilets flushing and power back on immediately, that we're not given an opportunity to do things right and rebuild in a more resilient fashion because of that very point. And, you know, one of the things that we've been trying to focus on is, as I said earlier, goal one, I call it a true culture of preparedness, is we've got to go back and holistically review how we ask people to be resilient or prepared. And if you look at the amount of assistance that we put in the hands of citizens that were impacted by disasters over the last year and a half, the numbers are off the charts. It's millions of people that have received, I think it's probably over six or seven million people in the last year and a half that have received money physically in their hands as a result of FEMA assistance. Well, the reason that they get that funding is typically they're uninsured, underinsured and not even remotely financially resilient or prepared. And so we're trying to go back and change our audience to work with financial advisors, educators, realtors, insurance agents on trying to teach people how to become more financially resilient, to have rainy day funds, but then also to be properly insured. So what we just saw with the Paradise wildfires, which was the worst disaster I've ever seen in my life, is that people who are struggling in retirement financially are paying off their mortgages and then letting their fire insurance lapse. And then it becomes FEMA's problem to help them get back on their feet and kick-start the road to recovery, but FEMA can't make them whole. So there's fundamental problems with finances in the wake of what I call asset poverty or what's known as asset poverty, where people are spending more money than they make and it's not allowing them to be properly prepared from a finance standpoint. It puts more pressure on our agency. So we're having to go back and fix fundamental core problems and work with other entities to help us do so. And we got to get back into the schools and start educating people no only on that aspect, but wherever you live, there are inherent risks that you have to be aware of and be prepared for, whether it's wildfires, hurricanes or earthquakes. Teaching realtors and those in the community that make communities work like realtors, and financial advisors and insurance agencies to start saying, "Hey, mitigated homes are valuable homes. Everybody should have flood insurance because any house can flood regardless of what the special flood hazard map says.” So there's a lot of things that we're trying to correct and a lot of myths out there that we're trying to correct about what citizens believe or don't believe when it comes to resiliency.

Shea Tuberty: Those are big issues, Brock. I'm glad I don't have your shoes to wear, but I think this comes down to … one of the things that's becoming more and part of the message here at App is in the sustainability culture, is educating students about privilege in the United States and how other folks in other countries don't have that privilege. What I'm talking about is sewage systems and houses with power all the time. We get to the point where we can't withstand 10 minutes of not having our cable connection, or our phone goes down, or our cell phones lose power. It's just the worst thing that can happen to you all day long, but it really isn't. I think it's only when we have these disasters that people are reminded that they're living in a chaotic world that they have no control over, but they convince themselves they do. I think your message that you're trying to get out through FEMA is the right one. I think that we need to get people on board with being prepared for anything, but I think the bigger issues is that we're living beyond our means these days and that comes with that privilege. You want more than your parents had. They expect more for you than they had, and that's a message that's not sustainable.

Brock Long: Shea, I couldn't agree more with you. The other fact of the matter is that the key to resiliency is not a bigger FEMA, or bigger response, or better response. The key to resiliency is local officials starting to get elected because they want to pass building codes, land use planning and zoning, and smart development. We're quick to blame climate change. I believe the climate is changing. I believe climate variability and other intrinsic cycles since the 1850s, since we've been measuring data through the National Weather Service reveals when we go through periods of increased and decreased periods of activities, like hurricanes or whatever else, but ultimately, we have to accept the fact that the United States has some of the most dynamic weather patterns of anywhere on the globe and we've got to develop in a more smart fashion to be able to live with those. And urban sprawl is putting people in harm's way. The built environment obviously increases the flood plain. And we just really have to be a lot smarter about the way we develop in the future, because I'm telling you, FEMA is running on all cylinders and the wheels are about to fall off with the number of disasters that we're having. Bigger FEMA is just not the answer.

Shea Tuberty: Yeah. I see your point. The data's out there. There's so many folks in the geography and planning department, in the appropriate technology, in the built environment. There's so much information that we're generating every day with student and faculty research, and not just at App. Many, many academic institutions have kind of taken this as their main strategic plan, but folks just aren't using it, and it's the most frustrating part going to a conference where you got the world leaders in some particular areas of science talking about what we could be doing and how much more power we would have moving forward, yet you go to your local community politicians with those ideas, and like you said, unless you have the right ears to listen to it, they just A, won't put you in a situation where you can even talk to them, or if they hear it, they just don't have the power to make any changes — at least they don't think they do.

Megan Hayes: One of the things that, just listening to the two of you talk, first of all, I'm a little embarrassed that I was a little irritated that Walmart was closed the other day and now that you're talking about the lack of patience and privilege that we have. But I think that's an important thing to think about. Shea, I guess this question is for you to at least begin talking about. What is our role as a university to build resiliency in the young people who are here learning everyday on our campus so that they understand that we're in a chaotic world and they don't necessarily expect their parking space to be plowed within five hours of two feet of snow falling, or have the problem solving skills in order to be able to negotiate when their exams take place so that they can, when they graduate and face some of these other difficulties that they're inevitably going to encounter?

Shea Tuberty: So that's a great question, and I think two things come to mind easily that happen here at App as far as kind of celebrated efforts on campus and their impacts on students. One of them would be service learning, and the other one would be the international travel and education efforts on campus. Let me tell you why. With service learning through the ACT program, the Appalachian and Community Together efforts, that take students out of the classroom. I think the classroom is part of that ivory tower culture where everything's perfect, faculty explain how things could be perfect if only we did this or that and some of the things we're talking about here. But if you take them out of the classroom and show them real people with real issues, and then have the students talk to them and say, "How did you end up here at this homeless clinic?" “Oh, well, my house went under water, or it burnt down in the fires we had last fall because of the droughts.” Then you realize these people had normal jobs, all their kids were in school, they could have been their neighbors. So, students realize that they're only one step away from that. The difference might have been that they didn't have insurance or they did have insurance. Then on the international side of things, you can take students out of their comfort zones here in the United States where you'll take them to communities in developing countries. Last year I was in Belize, the year before in Puerto Rico, just before the hurricanes hit. The students even then, even when things were working on all cylinders in those countries, the students were still amazed that with such little resources, these folks could live happy lives. In many ways, you can measure it, were happier than my students were that have arguably everything they need. So I think that taking them out of their comfort zones, letting them witness that this is out there, changes them forever. One of the unexpected outcomes of the Belize trip last year is we had a rainy day. We couldn't go scuba diving off shore — talk about privilege. But instead, we picked up a bunch of trash bags and cleaned up the reef front right where we were staying on this little barrier island. The kids picked up 30 bags of trash in 45 minutes.

Megan Hayes: Wow.

Shea Tuberty: I mean big trash bags. They were in tears while they were doing it because they just realized that what they were doing was hardly going to make a dent. And all of that trash had ended up on that beach since the last class had visited the island a week ago.

Megan Hayes: Oh my gosh.

Shea Tuberty: This is what's coming ashore from a number of different sources, but including big cruise liners that are just dumping their trash at sea. Everything we're picking up are like plastic toothbrushes, disposable forks and spoons and knives, flip flops, sunglasses. It was this incredible bulk of stuff that was coming in.

Brock Long: Megan, I think what are we teaching students at Appalachian, and not only that, but what type of education are they getting from the K through 12 up? And particularly, I go back to financial resiliency. The primary gap and driver of the assistance that we put out is no insurance.

Megan Hayes: Brock, this is for all income, right? This crosses socioeconomic levels?

Brock Long: It does. It's not poverty; it's asset poverty. It's people that make six-figure salaries that spend more than they make and then they try to cut their cost, they're highly leveraged, and so therefore they're not properly insured. They're not insuring their businesses or their homes properly. Some of the statistics are just absolutely mind-boggling. I've seen one that says 70 percent of Americans can't put their hands on $500 and it's not because they make a salary underneath the poverty level. They make decent salaries, they've just never been taught how money works, they've never been taught the power of compounding, they've never been taught how insurance works or credit works. The credit score of every Appalachian student is one of the most important scores that they'll ever have in their life. We spend a lot of time in schools, rightfully so, teaching them about how the human body works and that how you break down the human cell and the parts of it, mitochondria is the battery pack that powers a cell or whatever, but we're not teaching them the fundamental basics of how the world works when it comes to money and insurance. We often advocate that you ought to have four to six month's worth of operational cash in an account, in a safety account in your own rainy day fund, and then you invest everything after that, as much as you can. To talk about the credit score, we got to think differently to tell you how important this is. We work with a nonprofit called Operation Hope that provides free credit resiliency education to people who are really struggling but want to achieve financial resiliency.

John O'Bryant, who's had to break negative cycles that he grew up in, his parents didn't know how money worked and he talks about it, but he refers to the most recent Baltimore riots or the LA riots where communities end up burning down as a result of civil disturbances. He touts a statistic that says that no community with a collective credit score above 700 will have to deal with civil disturbances and having their city burned down. So think about that. Instead of saying we need more police to prevent riots or civil disturbances, actually what we need is we need to raise that community's collective credit score above 700 to prevent that stuff from happening. So it's a holistic change in the way that we are asking people to prepare, because what's happened with FEMA is that our be ready programs of asking people to go out and buy supplies for three to five days to be ready for the snow storm or the hurricane has become an unrealistic financial ask that nobody's doing either. We see challenges when it comes to asking people to evacuate. Hey, we need you to go buy a tank of gas, drive a couple hundred miles down the road and find a hotel to stay in. It's become an unrealistic financial ask for a majority of Americans, and it's not because they live in the poverty rate. It's a fundamental change, and what are we teaching freshman coming into Appalachian State, in my opinion.

Megan Hayes: Yeah. I think that what you two are hitting on, we started this conversation talking about environmental resiliency, but we see this huge social impact as a result of natural disasters and huge economic costs. So Shea, on our campus, we teach and conduct research about sustainability using those three pillars —environmental resiliency, social resiliency, economic resiliency. Can you talk a little bit more about how, how they go hand in hand? I'd like to hear both of you, actually, talk a little bit about that and how that plays out.

Shea Tuberty: I think Brock has made some really good points about folks connecting the environmental impacts on people's personal holdings and the impacts on their prosperity. So I think it's easy to make links between the three. It's an effort in EPA. They've got these grants called P3 grants, which is people, planet and prosperity. The idea is that you can create engineering and scientific approaches to handling old problems that might be both a solution to an environmental issue and also create some income or prosperity for a group of claims or stakeholders that are using it. So, another great example is using alternative energies that are taking a waste product and converting it into something else, either for energy or a product. So there's lots of low-hanging fruits to explain these kinds of situations, but basically, in the end, it comes down to humans are a part of the ecology everywhere we exist. We can't separate ourselves from the environmental impacts we're creating. So when the fish get sick, so are we.

I think there's been an interesting effort in the toxicological world. I'm an aquatic toxicologist and the conference I was just at in Sacramento, funny enough, the week that the campfire started in Paradise. The last day I was there I was smelling the fires. So I left just before it really got bad, but there was something called One Health that basically looks at human health issues and environmental health issues and correlates them to the same causation. It gives you more power moving forward when people realize that we're all connected in some way or another. I think the three pillars are critical for people to understand. I think it's kind of an academic thing to help people make connections between them. Once you've done it once or twice with some case studies, they start to do it on their own. I think they start to see that it's not that big a jump. They can start to see the impacts, possible impacts of some of the activities they're invested in or not invested in, behaviors and their impacts. So, it's kind of easy to make those connections once you've taught people how to do that. I think that's a critical skill set moving forward in the sustainability movement.

Megan Hayes: And Brock, it seems like you've been a firsthand witness to that for close to 20 years now.

Brock Long: Yeah, absolutely. I've seen way too many communities devastated, but a lot of it boils down to a lack of community resiliency approach or mitigation approach. If you look at all the construction that was done in vulnerable storm surge areas from basically Texas to Maine. When we go through periods of increased and decreased hurricane activity, through whether it's thermohaline circulation cycles or El Niño, the bottom line is that we seem to fail to recognize that hurricanes continue to hit and will always be a part of living in the southeastern United States and the Gulf. Therefore, why are we not putting in proper land use planning and building codes?

One of the most frustrating things is the state of Florida just struck down one of the most robust building codes in the country, the 2001 Florida Building Code. But you can see when Hurricane Michael impacted the areas and the other storms like Irma last year, anything built after 2001, after Hurricane Irma impacted the state, survived and did pretty well. Anything built before that time did not perform very well. But yet, the state legislature, as I understand it, struck the law down last year. It makes no sense. I call it hazard amnesia. We continue to not learn from these events and change building codes in a meaningful way.

The predicament that it places FEMA in is with all of the funding that we put out, my annual budget's roughly $16 billion dollars. At what point does FEMA say, "All right, no more money until you pass a robust building code that fits the hazards associated with your state or your community?" And we just start withholding the money back to force that change, almost like holding a gun to a community's head to do it. It's not the optimal way of going, but if we're not going to have communities proactively start electing officials and putting plans in place that are holistic in nature, a whole community plan for mitigation, then unfortunately, that's where I think government's got to go is to start driving this so that we're not through this vicious cycle again and again and again.

One of the biggest problems that I see is, I love the sustainability movement, particularly when it comes to power. I love to see green energy being put up, but I can tell you that every community I've seen where green energy is prevalent, none of it is mitigated for the disasters that the area faces. If you look at the solar panels, if you look at the wind turbines in Puerto Rico, they were all blown out. That is not easy infrastructure to put back into place. It's not as easy as stringing lines. Even the sustainability efforts of putting green energy into these communities, we're already doing it in an unmitigated fashion.

Megan Hayes: We're getting close to time. There's one question I wanted to ask you, Brock, in particular because you had brought up climate change earlier. I'm interested in how FEMA builds climate change impact research into its operating and strategic planning.

Brock Long: It's not so much climate change as much as it is climate variability. We look at cycles such as El Niño, La Niña, thermohaline circulation of the ocean's conveyor belt. There are definite patterns that increase and decrease activities. The question about it changing climate is, how does the change in climate impact those variability cycles that we know exist that impact our communities? For example, El Niño oscillates every five to seven years. Well El Niño, to me, means less hurricanes in the Gulf and in the Atlantic Ocean, but it means freak nor’eastern snowstorms in the winter and tornadoes in places that don't likely see tornadoes all the time. We look at trends inside FEMA. I combined our office of mitigation, our continuity office, which has an incredible mission of making sure that the government works on its worst day, whether we're attacked by another country or it's just whatever Mother Nature throws at us. I combine continuity mitigation and preparedness into one division, called a new division of resilience. What we've got to do is make an investment into climatology and better understanding the impact. But here again, regardless of what causes the disaster or the frequency of disasters to FEMA, regardless of what causes them, we're still on the hook for responding and trying to mitigate it.

Megan Hayes: So, Shea, can you talk quickly? One of the things that has been really interesting to me is listening to you and Brock talk about not only that national level, but that local level in terms of government and the role of government. So can you talk about why you see it's important that government agencies, whether they're federal government agencies or whether they're local, utilize that type of thought process and climate change impact or climate impact research in planning and prevention?

Shea Tuberty: Yeah. I think that the importance of the climate change movement is basically that this isn't going away. This is going to be more prevalent. So when you say, "What's climate change mean to your region?" Here it means that the rainfall levels over the course of a year may not change. So the totals may not change, but the intensity of the rainfall events is going to change. So we get more flooding events and so it's happening more commonly. Those are the biggest issues we deal with. So how do you get your local government to think about the long game? How do you change … you know, Brock's made a big point about getting folks on board with creating building rules that are going to be protective of the long game. So trying to make buildings more sustainable. The problem with the way our politics run is that we're changing our people out every couple years. So you have to retrain the new untrained folks about the long game. So every four to eight years, you're basically getting a changeover of the guard and those guard are responsible for continuing the long game, but that's not happening. I think the amnesia that Brock talked about, that's a great term, that's exactly what it is. It doesn't take very long for people to forget the damages that were done, and then you also got people moving constantly. It's a different world where everybody's moving from place to place. When they're doing that, they don't come with that institutional memory of, OK, this hurricane's going to hit here within the next five years. I can't build there. They just come in, spend a million dollars, put a house on the beach, and then it's gone the next year and they're like, "Oh, no one told me." So it's getting the locals to think about the long game, and then building the infrastructure in a way that's going to be sustainable and it's going to be able to be there in 100 years. I think that's where we're at, and I think getting those people in place is going to happen in the next generation because the kids that are in school now are getting it left and right. I feel belittled by my students often because I'm not doing something they think is normal practice for a sustainable world, although I'm the one teaching it. I love that. They push us harder and harder. I think there's good things coming in the future that way.

Megan Hayes: Brock, are you optimistic about the future?

Brock Long: You have to be. You have to be. And you know what? I'm optimistic because finally I think Congress has listened. As I said earlier, I think I've testified 14 times now, but the first 12 of those testimonies was geared towards, we got to do more in pre-disaster mitigation and Congress acted. The Disaster Recovery Reform Act catapults pre-disaster mitigation in the front. Now what that means is that we got to get local governments to start putting aside the match money for those grants and then really think through the mitigation strategies that would improve their communities, that would keep the roadways open, keep the communications infrastructure running, keep the power and fuel running, making sure that their health and medical capability doesn't collapse in the face of disaster — just making sure that we're being smart with the way that we're expanding those communities. Yeah, I'm excited. I think people are starting to work together and I think we just have to, at some point, agree to disagree on the exact cause or whatever, but realize that we all got to do a lot more to mitigate and become resilient.

Megan Hayes: Before I wrap this up, do you two have anything that you didn't not say that you'd like to get into this conversation?

Shea Tuberty: I'd just like to thank Brock for his leadership at the national level. I think a lot of us that know you're in that position are really happy that you came from App. That's another feather in the cap of the kind of students that we generate and the kind of leadership that we have here in our small town of Boone that has impacts worldwide. So keep doing what you're doing, Brock, and I thank you for those 14 times in front of Congress. I know that must have been really tough to do. Keep sending the same message, I think eventually people start to hear it. It helps when you have more catastrophes, you know? So it's always getting worse before it gets better.

Brock Long: Shea, Megan, it's been an honor to be on this podcast. I hope we can do it again. You know the doors to FEMA are open. So, if there's anything that we can do to help Appalachian State students, come on up. We'd love to see you and show you what we do. Part of the problem is a lot of people don't understand FEMA's role, but it's very complex, and it's only becoming harder every day until we start fixing some fundamental problems that exist in our communities. So, thank you. It's been an honor.

Megan Hayes: Well, thank you both. This opportunity to speak with an esteemed and distinguished alumnus and also an esteemed and distinguished faculty member has been my distinct pleasure. So, thank you so much. I heard the beginnings of a conversation under a tent at homecoming weekend and have been really excited about the possibility of being able to continue that conversation or at least listen to it a little bit more from my perspective. So, I appreciate the work that both of you do very much. I think that it's making a really big difference in our nation, in our world and the future of our planet. So, thanks to both of you.

Brock Long: Thank you.

Shea Tuberty: Thanks for organizing this, Megan.

What do you think?

Share your feedback on this story.

Appalachian biology professor Dr. Shea Tuberty and former FEMA Administrator Brock Long discuss how developing a culture of preparedness fosters resiliency

About Appalachian State University

As a premier public institution, Appalachian State University prepares students to lead purposeful lives. App State is one of 17 campuses in the University of North Carolina System, with a national reputation for innovative teaching and opening access to a high-quality, cost-effective education. The university enrolls more than 21,000 students, has a low student-to-faculty ratio and offers more than 150 undergraduate and 80 graduate majors at its Boone and Hickory campuses and through App State Online. Learn more at https://www.appstate.edu.

![How NCInnovation Is Rethinking Economic Development in North Carolina [faculty featured]](/_images/_posts/2026/02/rethinking-economic-development-600x400.jpg)