BOONE, N.C. — Each year, Americans manage the effects of 100,000 thunderstorms; 26,000 severe thunderstorms; 5,000 floods; 1,300 tornadoes; and two deadly hurricanes that make landfall, leading to 650 deaths per year and about $15 billion in damage, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Approximately 98 percent of all presidentially declared disasters are weather-related.

For many, the presence of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) during these events and their aftermath is a given. Their emblazoned jackets are a standard fixture in media imagery of disaster recovery scenes. A federal agency with a budget north of $16 billion, FEMA has a mission statement that simply reads “helping people before, during and after disasters.”

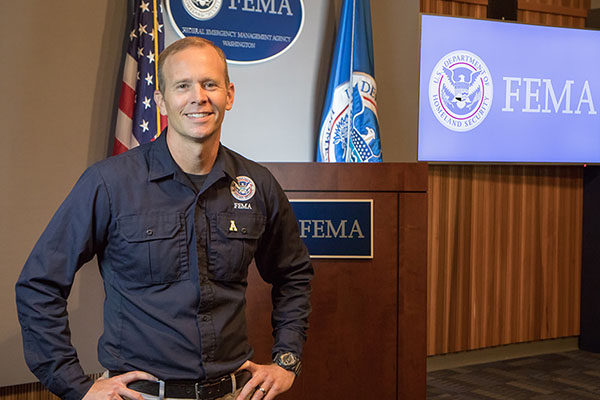

Communities that face devastation seek to recover and rebuild, and the presence of FEMA, with its recovery and relief expertise — and its funding — is an expectation during and after disaster. Appalachian alumnus Brock Long ’97 ’99 led the agency from April 2017 to March, streamlining its mission and focusing its emphasis on resiliency.

Long reported that, since spring 2017, FEMA has rendered more individual and public assistance than in the previous 38 years combined. “That’s our entire history basically packed into a year and a half,” he said.

The assistance, Long said, came in the form of “money to those who are uninsured, to (recover from) devastating losses, for public assistance and money that goes into fixing infrastructure.”

“Unfortunately, we’re in a vicious cycle of communities being impacted by disasters and having to constantly rebuild,” Long said, “and it’s almost as if we’re not learning anything from what Mother Nature and history have taught us.”

During his tenure leading the agency, Long focused heavily on the “before” aspect of FEMA’s mission. Experts at FEMA and in local governments and communities have determined planning and preparation can make the biggest impact on mitigating the costs associated with disaster.

Long emphasized individual preparation — the kind that goes beyond buying a generator and stocking up on canned food and bottled water.

“I think that we need to get people on board with being prepared for anything, but I think the bigger issue is that (as a society) we’re living beyond our means these days … You want more than your parents had. They expect more for you than they had, and that’s not sustainable,” he said. “It’s a holistic change in the way that we are asking people to prepare.”

In 2018, the Federal Reserve Board reported that 40 percent of U.S. adults would not be able to cover a $400 emergency without borrowing money or selling assets. In Long’s experience, it is often not financially feasible for people, regardless of socioeconomic status, to evacuate — even when that is the best option to ensure their personal safety.

Developing a culture of preparedness

“When it comes to asking people to go buy a tank of gas, drive a couple hundred miles down the road and find a hotel to stay in … that’s an unrealistic financial ask for a majority of Americans,” said Long, noting that the lack of a preparation mindset also means many Americans are also underinsuring their homes and businesses. “So, we’re trying to develop a true culture of preparedness.”

This emphasis on preparedness culture extends beyond individual preparation. Data show when government, residential and commercial entities prepare for weather-related impacts, they can withstand the aftereffects and bounce back more effectively afterward. The National Institute of Building Sciences released a study in 2018 that found every $1 spent on federally funded mitigation grants saves the nation $6 in future disaster costs. At the local level, the same report indicated that building new construction to exceed standard hazard mitigation requirements can save taxpayers $4 for every $1 spent.

Under the Disaster Recovery Reform Act of 2018, Long said 6 percent of recovery dollars spent by FEMA will now be allocated to pre-disaster mitigation. “For the first time in history, we have put a massive bulk of pre-disaster mitigation on the front end … to ultimately save lives and reduce the impact of disasters on infrastructure and property.”

To create resilient communities, Long said, “it’s going to take different approaches.”

Resiliency work is sustainability work

Dr. Shea Tuberty, an Appalachian biology professor and the Department of Biology’s assistant chair for student affairs, is a water quality expert with a passion for sustainable management of water resources. His teaching, research and community outreach emphasize resiliency.

For Tuberty, resiliency work is sustainability work. “I use that term almost interchangeably with sustainability,” he said. “Building infrastructure to withstand a catastrophe and then respond quickly afterwards with continued capability requires an interplay of environmental, social and economic resiliency.”

Appalachian’s location in one of the highest mountain communities in the Eastern United States offers Tuberty an important location for his work studying water quality and teaching students to measure and understand the impact of reduced water quality at or near the source of water for communities downstream.

Tuberty said the number of flooding events in the High Country in 2018 set a 40-year record. “These events impact town and county operations, folks that are living in the flood plain and even university operations are impacted significantly,” he explained.

Tuberty said past restoration projects on campus and in the Boone area have been focused on aesthetics rather than on preventing future problems. “There are a number of us in the natural sciences that look at these efforts as Band-Aids,” he said. “So, (resiliency) is something the chancellor has got her eye on.”

A philosophical change is taking place in the preparedness mindset on campus. “Our emergency management office on campus is starting to plan for the future,” Tuberty said. “On the horizon, we’re talking about daylighting the creek on campus and decreasing the footprint of Peacock Parking Lot. We could park more cars in a smaller footprint, open up more grassland and create some wetlands that would be aesthetically pleasing and also functional.”

Beyond changes to the physical infrastructure of campus, Tuberty also cited service-learning and international travel as two approaches Appalachian takes to help students develop personal resiliency skills.

“The classroom is part of that ivory tower culture where faculty explain how things could be perfect if only we did this or that,” Tuberty said. Through service-learning, he explained, students begin to understand how they can apply classroom knowledge to complex situations in a real-world environment.

Real people with real issues, Tuberty said, can teach students about the complex and devastating impacts of a natural disaster. By working to help stricken families in relief shelters, “students might realize these people ... could have been their neighbors. (They may) realize they’re only one step away from that; the difference might have been that they didn’t have insurance.”

International travel, especially to communities in developing countries, Tuberty believes, is also an important learning opportunity.

“Last year I was in Belize, the year before in Puerto Rico. My students were amazed that with such little resources, these folks could live happy lives. In many ways you can measure, they were happier than my students who have, arguably, everything they need. Taking them out of their comfort zones, letting them witness this — it changes them forever.”

Optimism for the future

“Our students push us harder and harder,” said Tuberty, who noted his students regularly challenge him to think differently about practices “they think are normal for a sustainable world, although I’m the one teaching it. I love that. I think there are good things coming in the future.”

From Long’s perspective, changing the preparedness mindset at the federal level is starting to pay off. After more than a dozen congressional testimonies related to pre-disaster mitigation, he sees a “sea change.”

“We just have to, at some point … realize that we’ve all got to do a lot more to mitigate and become resilient,” he said. “Yeah, I’m excited. I think people are starting to work together.”

What do you think?

Share your feedback on this story.

Q&A with Walker College of Business’ Dr. David Marlett

About the Department of Biology

The Department of Biology is a community of teacher-scholars, with faculty representing the full breadth of biological specializations — from molecular genetics to landscape/ecosystem ecology. The department seeks to produce graduates with sound scientific knowledge, the skills to create new knowledge, and the excitement and appreciation of scientific discovery. Learn more at https://biology.appstate.edu.

About the College of Arts and Sciences

The College of Arts and Sciences (CAS) at Appalachian State University is home to 17 academic departments, two centers and one residential college. These units span the humanities and the social, mathematical and natural sciences. CAS aims to develop a distinctive identity built upon our university's strengths, traditions and locations. The college’s values lie not only in service to the university and local community, but through inspiring, training, educating and sustaining the development of its students as global citizens. More than 6,800 student majors are enrolled in the college. As the college is also largely responsible for implementing App State’s general education curriculum, it is heavily involved in the education of all students at the university, including those pursuing majors in other colleges. Learn more at https://cas.appstate.edu.

About Appalachian State University

As a premier public institution, Appalachian State University prepares students to lead purposeful lives. App State is one of 17 campuses in the University of North Carolina System, with a national reputation for innovative teaching and opening access to a high-quality, cost-effective education. The university enrolls more than 21,000 students, has a low student-to-faculty ratio and offers more than 150 undergraduate and 80 graduate majors at its Boone and Hickory campuses and through App State Online. Learn more at https://www.appstate.edu.

![How NCInnovation Is Rethinking Economic Development in North Carolina [faculty featured]](/_images/_posts/2026/02/rethinking-economic-development-600x400.jpg)