According to the National Weather Service, Hurricane Helene made landfall in the Big Bend area of the Florida Gulf Coast as a Category 4 storm late in the evening of Sept. 26, 2024. The storm reached the Southern Appalachians on Sept. 27, 2024, causing widespread flooding, landslides, downed trees and power outages. Image courtesy of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration/Cooperative Institute for Research in the Atmosphere

BOONE, N.C. — In September 2024, Hurricane Helene brought record-breaking rain and wind to the High Country, leaving a lasting impact across the region. It marked Boone’s most devastating flood event since 1940 — and before that, 1916.

“Since we’ve been recording weather in Western North Carolina, it’s the most dangerous and impactful disaster ever,” said Dr. Shea Tuberty, professor in Appalachian State University’s Department of Biology and director of App State’s Quality Enhancement Plan, Pathways to Resilience.

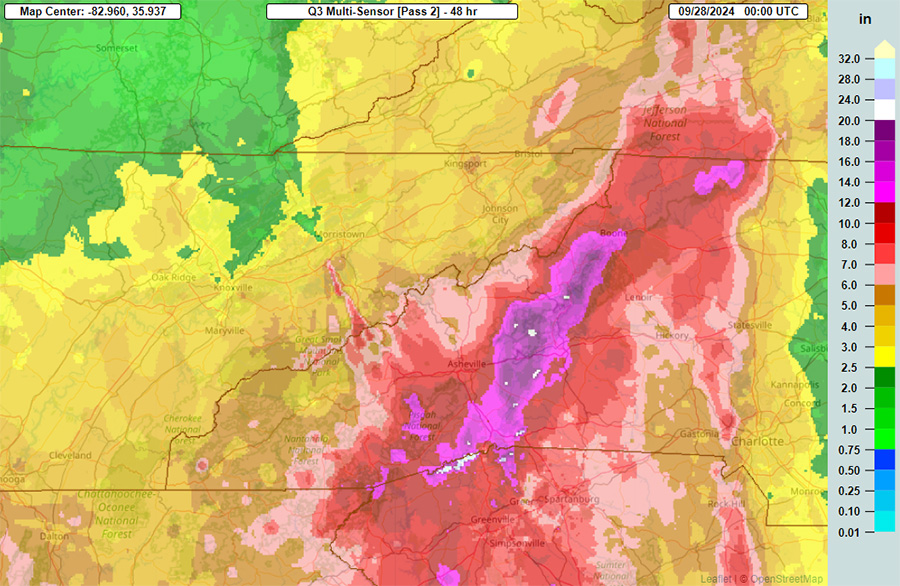

According to the National Weather Service, Hurricane Helene — combined with a band of heavy rain that preceded the storm’s arrival — dropped upwards of 30 inches of rain in some areas of the Southern Appalachians and around 10 to 20 inches of rain across most of the High Country. Wind gusts ranged from 40 mph in valleys to more than 100 mph on some mountaintops. These elements triggered widespread flooding, landslides, downed trees and power outages.

The North Carolina Office of State Budget and Management estimated $59.6 billion in damages across the state — nearly four times the impact of Hurricane Florence in 2018. The documented impacts are staggering:

- 4.6 million people — more than 40% of the state’s population — lived in one of the designated disaster areas.

- More than 100 people died from the storm.

- Thousands of homes were destroyed, and tens of thousands more were damaged.

- Thousands of miles of roads and bridges were damaged.

- Millions of people lost access to water, electricity, telecommunications and health care facilities.

According to the National Weather Service, total two-day rainfall estimates by radar ending the evening of Sept. 27, 2024, were in the range of 12 to 20 inches in a large swath of Western North Carolina, with a few places estimated to have received over 20 inches. Image courtesy of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration/Cooperative Institute for Research in the Atmosphere

“When it hit, it just hung around — and that’s actually fairly typical for the mountains, for storms to stick in place,” said Dr. William Anderson, professor in App State’s Department of Geological and Environmental Sciences. “Since the ground was already saturated before the hurricane, then you get one to two feet of rain in a very short period of time — you’re kind of asking for trouble.”

Anderson attributes these quick and heavy downpours to the orographic effect — a phenomenon in which air flow is disrupted by mountains, leading to changes in weather patterns and increases in rainfall.

Dr. Christopher Thaxton, professor in App State’s Department of Physics and Astronomy and director of the university’s atmospheric science minor, said that while projections for Boone called for very high rainfall totals, many locals were still surprised by the storm’s immense impact.

“It’s hard, because existing weather models don’t always do a good job of representing weather in the mountains,” said Thaxton. “Most models have been developed for places that are nice and flat, because the equations are a lot easier to solve. It certainly places a lot of value on local forecasts that use historical information and knowledge of the Southern Appalachians to give more accurate predictions.”

Tuberty — who lived in hurricane alley for more than a decade, including in New Orleans and Pensacola, Florida — echoed that sentiment, emphasizing the importance of keeping a close eye on local weather, even in areas not typically prone to disasters such as Helene.

From steep slopes to narrow floodways, mountains have unique hurricane hazards

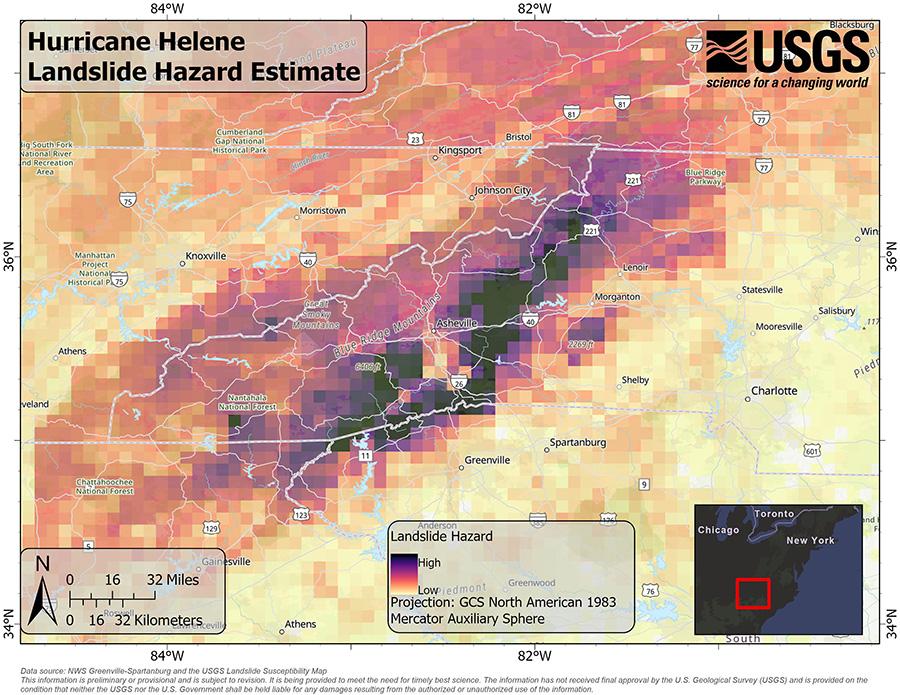

Hurricane Helene’s historic impact extended far beyond flooding. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, the storm triggered more than 2,000 landslides in less than a week.

Anderson said landslides are one of several factors that make hurricanes uniquely dangerous in the mountains, where steep slopes and narrow floodways cause damage to occur much faster than on the coast.

“In the mountains, when you get these big rainfall events, the water level is going to rise — but it’s also going to drop very quickly because of that steep slope — and that’s how we get all of these flash floods,” he said. “When a big storm hits the coastal plain, it’s a different story that can persist for weeks.”

Anderson explained that in the mountains, water often moves much faster than in coastal floods because of the steep slopes. This rapid flow erodes banks and hillsides quickly, which is the primary reason so many landslides occurred and trees came down during the storm.

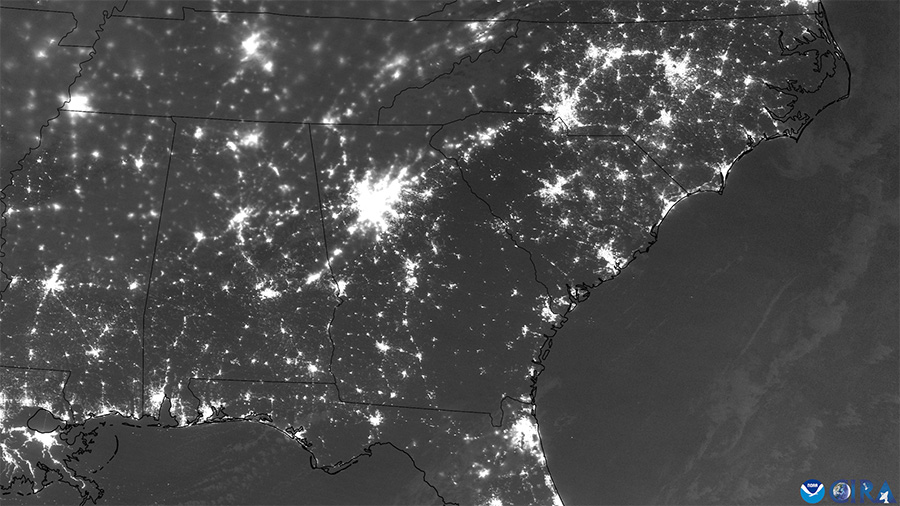

This image, taken from space by a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration satellite on Sept. 28, 2024, shows the darkness from power outages in the Southern Appalachians after Hurricane Helene. When the storm struck, it knocked out electric service to about 5.5 million customers, and in Western North Carolina, some remained without power for several weeks. Image courtesy of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration/Cooperative Institute for Research in the Atmosphere

Another unique impact the hurricane had on the region was the devastation to bridges, which were among the hardest hit infrastructure. According to the North Carolina Department of Transportation, nearly 7,000 roads and bridges were damaged from the storm.

“A lot of bridges here connect communities, so when they were destroyed, people were isolated,” said Thaxton. “A lot of the small, family-built bridges just aren’t designed to take it. To put it in perspective, even some state bridges were blown away.”

Tuberty said that in a region that doesn’t experience natural disasters like this very often, damages can escalate from a lack of foresight and preparation.

“Because of the history of flooding along the coast, most places have learned their lesson and haven’t built right against the water like you have here,” he said. “In our area, you will see houses with a stream underneath the back porch — literally over the water — and those places didn’t make it.”

Tuberty added that building homes in hazardous areas is a common issue in the mountains — but sometimes it can’t be avoided.

“All the landslides happened in places that would have been predicted, and probably those houses were built on previous landslide debris fields — because that’s the only flat place they could find,” he said. “Building toward better resiliency in the future might mean that there’s better policy about where you put your homes.”

Looking ahead, Anderson anticipates Western North Carolina could become even more susceptible to flooding and landslides due to landscape changes following the storm.

“Think of how many trees have come down,” he said. “Because of their roots, they’re pretty good for slope stability, and they add cohesion to the soil. All the ones that have blown over or that we’ve pulled out are going to decay over time. So we’re going to lose that added strength, and that will likely cause more slope failure down the line.”

Tuberty added that because of this, restoration experts point to replanting along streams and steep slopes as a key priority for the area’s recovery.

According to the National Weather Service, Hurricane Helene — combined with a band of heavy rain before the storm — dropped upwards of 30 inches of rain across the Southern Appalachians. Pictured is a view outside of App State’s Rankin Science building after the storm, an area that was heavily impacted by flooding. Photo by Wes Craig and Chase Reynolds

A warmer atmosphere holds more water — and stronger storms

Both Tuberty and Thaxton agree that storms such as Hurricane Helene are becoming more intense and more frequent due to the warming of the atmosphere.

“A warmer atmosphere holds more precipitable water,” Thaxton said, “which leads to higher rainfall amounts, higher rainfall rates and greater intensities associated with storms such as this.”

Tuberty explained that because of temperature changes that have already occurred over the past several decades, Helene carried an estimated 10% more water than it would have in the past — and wind speeds were more than 10% stronger.

He added that the standard predictions for storm return intervals — such as 1,000-year or 100-year storms — are proving to be inaccurate.

“By some measurements, this was a 7,000-year storm,” Tuberty said. “But it happened in 1916, and again in 1940 — so we’ve had three storms of this magnitude in just 110 years.”

According to the North Carolina State Climate Office, 2018 was the wettest year on record in Boone and the state, and 2020 was the second wettest. As for heat, 2019 was the warmest year on record, and 2024 was a close second. Overall, the data shows a slow but steady increase in both heat and precipitation over the past 100 years.

“By 2100 here in the Southern Appalachians, we’re not really predicting huge changes in temperature as much as we are predicting more intense precipitation events and flooding,” said Tuberty. “In 2018, for example, we had about 93 inches of rain, well above the average of 59 inches, and it all came in seven huge events.”

Thaxton noted that these increasingly intense bursts of rain are also countered by longer periods of drought, which bring on a whole new set of problems.

Helene sparks a call for disaster preparedness

With weather trends pointing to a greater likelihood of severe weather events in the region, Tuberty said it’s best to start preparing now.

“It made us realize we need to spend some time getting prepared for a week or two without power,” he said. “A lot of folks had no water or food and weren’t really ready at all. We quickly found out who the resourceful folks were — those who had chainsaws, tractors, generators, those sorts of things. This probably isn’t going to be a one-off thing, so I’d be surprised if people didn’t learn from this.”

Anderson said multiple researchers at App State have established monitoring networks and data collection systems to study Hurricane Helene and better predict future weather impacts.

“It’s so important to see long-term trends on what’s happening,” he said. “We can see how the landscape is changing, how rivers are being affected — all sorts of things. We are definitely working toward a better future, and science can help us learn and prioritize going forward.”

Since Helene, App State researchers have consistently worked to map landslide risks in the area, better understand flooding and its ecological impacts on rivers, track storms and atmospheric trends and much more.

Outside of research, and to look at the hurricane in a positive light, Thaxton said one of his biggest takeaways from the storm was the overwhelming sense of community it sparked.

“That sense of community — with people from very different political and economic backgrounds working together side by side — it’s inspiring,” he said. “It really drove a sense of home for me.”

Now, as the region rebuilds and researchers continue their work, one lesson from Hurricane Helene is clear: In the face of challenges, awareness, education and community matter now more than ever.

What do you think?

Share your feedback on this story.

About Appalachian State University

As a premier public institution, Appalachian State University prepares students to lead purposeful lives. App State is one of 17 campuses in the University of North Carolina System, with a national reputation for innovative teaching and opening access to a high-quality, cost-effective education. The university enrolls more than 21,000 students, has a low student-to-faculty ratio and offers more than 150 undergraduate and 80 graduate majors at its Boone and Hickory campuses and through App State Online. Learn more at https://www.appstate.edu.