BOONE, N.C. — Nocturnal, diurnal — or something different? Thanks to camera traps, a global study published in Science Advances and co-led by Appalachian State University’s Dr. Zach Farris shows that vast numbers of wild mammals are behaving differently than previously thought, with activity patterns that don’t match how science has classified them.

Farris, a faculty member in App State’s Beaver College of Health Sciences, helped lead the analysis of 445 mammal species on six continents to determine their daytime and nighttime activity patterns. He and his fellow researchers studied how numerous species — ranging from skunks, to cats, to elephants — are being forced to adapt to environmental changes.

“The research surprised us — we were able to prove that less than 50% of the species investigated matched with existing literature on their classification of diurnal (daytime) or nocturnal (nighttime) species,” said Farris, an associate professor in the Department of Kinesiology with a focus on wildlife conservation.

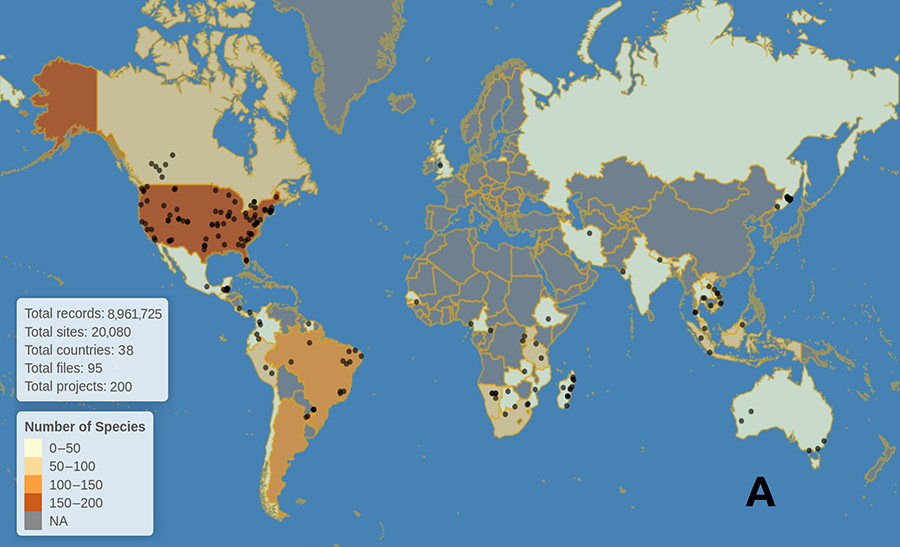

To generate their findings, Farris, along with co-authors and ecologists Brian Gerber, Kadambari Devarajan and Mason Fidino, collaborated with 217 other researchers to analyze 8.9 million images from 38 countries. The images were captured by 20,080 camera traps — automated cameras that capture images or videos of wildlife when triggered by motion, heat or other sensory input.

Their study, “When the wild things are: Defining mammalian diel and plasticity,” was recently published by the open-access, peer-reviewed journal Science Advances. It represents information collected by one of the most comprehensive camera trap dataset studies to date and yielded a searchable library of the results: https://shiny.celsrs.uri.edu/bgerber/GlobalDiel/.

“Mammals adapt, particularly when humans are present or their habitats have been disturbed,” Farris said. “We hope that our work on this issue will inspire other ecologists to continue studying mammals, expand the narrow classifications and continue to monitor the impact of habitat disruption.”

Farris and his co-researchers also developed a modeling framework for evaluating and comparing the observed activity patterns with published literature and assessing how human changes alter these patterns. The framework was published in the Journal of Animal Ecology, allowing other researchers to use it to evaluate their target species’ activity patterns, Farris said.

Changing habits close to home

The study included animals found in Appalachia, providing new insights into activity by such common residents as striped skunks, deer, gray foxes and many other species. An elusive denizen of Appalachia, the bobcat did not follow established behavior patterns well at all, Farris said. Classified most often as crepuscular or nocturnal — active at twilight or night — the bobcat exhibited movements that were, instead, more flexible, adapting to human activity.

“When we use camera traps, we observe bobcats being active during all periods of the day, and factors such as human activity or presence, distance to roads or forest edge and similar factors are what really play a role in what time of day we observe them being active,” Farris said.

The behavior of the cat family, in general, varied from its nocturnal classification, Farris noted. Deer were another example of a species not conforming to its traditional diurnal classification. Instead, cameras revealed they are active at all hours, with human presence being a primary driver of those patterns.

“Ask a local to give you a single diel period — day, night, dawn, dusk — when deer are out in their yard, eating up their plants or running out in front of their car, and you will get a different answer from everyone you ask,” Farris said.

Striped skunks were another striking example of this flexibility driven by humans. In areas with high human activity, the animals responded by using nighttime hours to cover their activity. Where humans were not present or active, the skunks were more likely to be out and about at all hours.

The findings have significant implications for the management of species, particularly conservation measures, according to the researchers. If human activity or other disturbances limit a species’ ability to access resources during the time of day they are active, for example, then a protected area is not protecting the species, only the resources, they wrote.

“Animal diel activity is well studied and established for most mammals globally,” Farris explained. “However, anthropogenic (environmental changes due to human activity) and ecological changes likely influence most, if not all, mammals globally.”

He continued, “This paper and its findings bring to light an issue most ecologists have known to be true but have not yet quantified and explored. These research findings will expand our knowledge and open discussions on previously used, narrow classifications of diurnal and nocturnal species.”

What do you think?

Share your feedback on this story.

About the Department of Kinesiology

The Department of Kinesiology at Appalachian State University, housed in the Beaver College of Health Sciences, blends scientific rigor with practical experience across the undergraduate and graduate levels, offering the Bachelor of Science in Kinesiology and the Master of Science in Kinesiology, along with an undergraduate minor in kinesiology. The programs’ innovative curricula prepare students for dynamic careers in health, fitness, performance and sport — shaping the next generation of evidence-driven professionals. Learn more at https://phes.appstate.edu/kinesiology.

About the Beaver College of Health Sciences

Appalachian State University’s Beaver College of Health Sciences (BCHS), opened in 2010, is transforming the health and quality of life for the communities it serves through interprofessional collaboration and innovation in teaching, scholarship, service and clinical outreach. The college enrolls more than 3,600 students and offers 10 undergraduate degree programs, nine graduate degree programs and four certificates across seven departments: Kinesiology, Nursing, Nutrition and Health Care Management, Public Health, Recreation Management and Physical Education, Rehabilitation Sciences, and Social Work. The college’s academic programs are located in the Holmes Convocation Center on App State’s main campus and the Levine Hall of Health Sciences, a state-of-the-art, 203,000-square-foot facility that is the cornerstone of Boone’s Wellness District. In addition, the college supports the Appalachian Institute for Health and Wellness and has collaborative partnerships with the Wake Forest University School of Medicine’s Physician Assistant Program, UNC Health Appalachian and numerous other health agencies. Learn more at https://healthsciences.appstate.edu.

About Appalachian State University

As a premier public institution, Appalachian State University prepares students to lead purposeful lives. App State is one of 17 campuses in the University of North Carolina System, with a national reputation for innovative teaching and opening access to a high-quality, cost-effective education. The university enrolls more than 21,000 students, has a low student-to-faculty ratio and offers more than 150 undergraduate and 80 graduate majors at its Boone and Hickory campuses and through App State Online. Learn more at https://www.appstate.edu.